APRIL DAN FENG presents the pros and cons of China’s Supply-Side Reform policy.

On November 10, 2015, during the Chinese Communist Party Working Conference on Economic Policies, President Xi Jinping introduced a series of policies to stimulate Chinese economy known as the Supply-Side Reform. Of the numerous policies, Xi emphasized the importance of cutting the state-owned enterprises’ (SOEs) sprawling over capacity and announced that the government would start ordering mergers of SOEs by pooling together their resources to obtain bigger market shares and more efficient operating structures. In short, the bigs are getting bigger, per government’s request.

Over the years, China’s SOEs have become less profitable, especially when compared with private enterprises. According to a national survey conducted in March 2015 by the National Bureau of Statistics, total profits of SOEs decreased by 37 percent compared to the year before, whereas profits of their private counterparts increased by 9.1 percent. However, SOEs continue to occupy a major share of markets and resources and overproduce under such inefficient privileges. In the steel and coal industries especially, almost half of the world’s yield is attributed to the overproduction of Chinese SOEs. Since the Deng Xiaoping administration, the Chinese Communist Party has been gradually reforming China’s economic structure by actively supporting private-owned firms through various policy combinations like transferring ownership of state-owned assets and setting up a budget system for managing state capital. The efforts on behalf of strengthening the private sector have definitely bore fruit. According to a report by the World Bank, growth of the private sector has steadily increased since the 1980s. In 2003, the private sector had grown to employ 74.7 million people, surpassing, for the first time, the 74.6 million employed by SOEs. Under such a trend, China’s economy has achieved unprecedented growth over the past thirty years.

However, Xi’s proposal of merging SOEs seems to flip the focus from empowering private enterprises to strengthening the state-owned sector. The president confidently argued that such efforts could further advance the efficiency of the market and provide benefits to consumers. But could it really?

***

Although the proposed supply-side reform could conceivably lower costs through merging, it cannot drive down prices without creating a more competitive market for the SOEs. In other words, these firms would have the resources but not the incentives to provide lower pricing.

In fact, mergers of SOEs inevitably reduce market competition by concentrating the market share of state-owned monopolies and raising the barrier to entry for private enterprises. On December 30, 2014, China’s two largest state-owned rail companies, China CNR Corporation Limited (CNR) and China South Locomotive & Rolling Stock Corporation Limited (CSR) announced that under government order from Beijing, they would merge to form China Railway Stock Corp. (CRRC). The newly merged company controls over 90 percent of China’s industry with a market value of $26 billion and a combined annual revenue of $32.3 billion, making it virtually impossible for smaller private enterprises like the Shenzhen China Technology Industry Group Corporation Limited to survive in the industry.

Since merging SOEs will almost inevitably reduce the number of competitors in specific industries and stymie competition between the private and the state-owned sectors. It is unlikely that the newly merged SOEs will lower prices. Thus, such a policy might end up hurting consumers—a problem that China, if it hopes to expand its domestic demand, should be wary of.

As the Chinese SOEs gain more say in both the domestic and the global markets, they face less competition in their respective industries and gain more bargaining power in setting prices at their will.

How can the Party address the long-lasting issue of SOEs slowing down market efficiency then? Professor Eva Dziadula from the University of Notre Dame provides an insight into the problem, “The reform should encourage competition and needs to be more market oriented. If you want to create incentives for growth, then benefits such as preferential tax treatments should also benefit the private enterprises.” Essentially, as Dr. Dziadula points out, the reform indeed should be on the supply-side, but the Chinese government has targeted the wrong suppliers. To truly benefit the consumers, it is best to help private companies thrive instead of equilibrating the market with the giant SOEs.

The key to solving the slowdown of market growth is to help private enterprises by ending the government-provided preferential treatments that SOEs receive. Since the 1960s, Chinese SOEs have enjoyed preferential treatment from the government in areas such as licensing, government contracting, and financing—ultimately securing an unfair competitive edge over private enterprises. Many leaders of SOEs have been found guilty of corruption and collusion with government officials. According to the official Xinhua News Agency, 115 business leaders of SOEs were arrested and charged with corruption in 2014 alone. Lack of market competition and corruption have worsened the SOEs’ efficiency. Only by ending the preferential treatments to SOEs can the government really achieve the important goal of allocating capital and resources fairly across different market sectors on the supply side. The new market structure would push some SOEs to merge and will increase the likelihood that they lower prices proportionally to their actual costs.

What are the motives behind the government’s proposal then? One guess is that such moves form national champions that can better compete overseas. Since the policy was first raised in December last year, there had been rumors of mergers of some of the biggest SOEs in the railway, telecom, steel and airline industries. According to the Wall Street Journal, a merger of China Railway Group and China Railway Construction will create a combined revenue of 1.2 trillion yuan, giving China a much greater say in the global market. The combined company of China Unicom and China Telecom has an annual revenue of 609 billion. A merger of Wuhan Steel and Baosteel would create the world’s No. 2 steel company by production. A merger of Air China and China Southern Airlines would create the world’s largest air carrier by fleet size. However, as the Chinese SOEs gain more say in both the domestic and the global markets, they face less competition in their respective industries and gain more bargaining power in setting prices at their will.

As the bigs go bigger, Beijing tightens its grip on key parts of world industry. In the next few years, however, under this shadow China casts on the global economy, the domestic consumers and private enterprises will still likely be struggling in the dark.

April Dan Feng is a junior at the University of Notre Dame. Contact her at dan.feng.13@nd.edu.

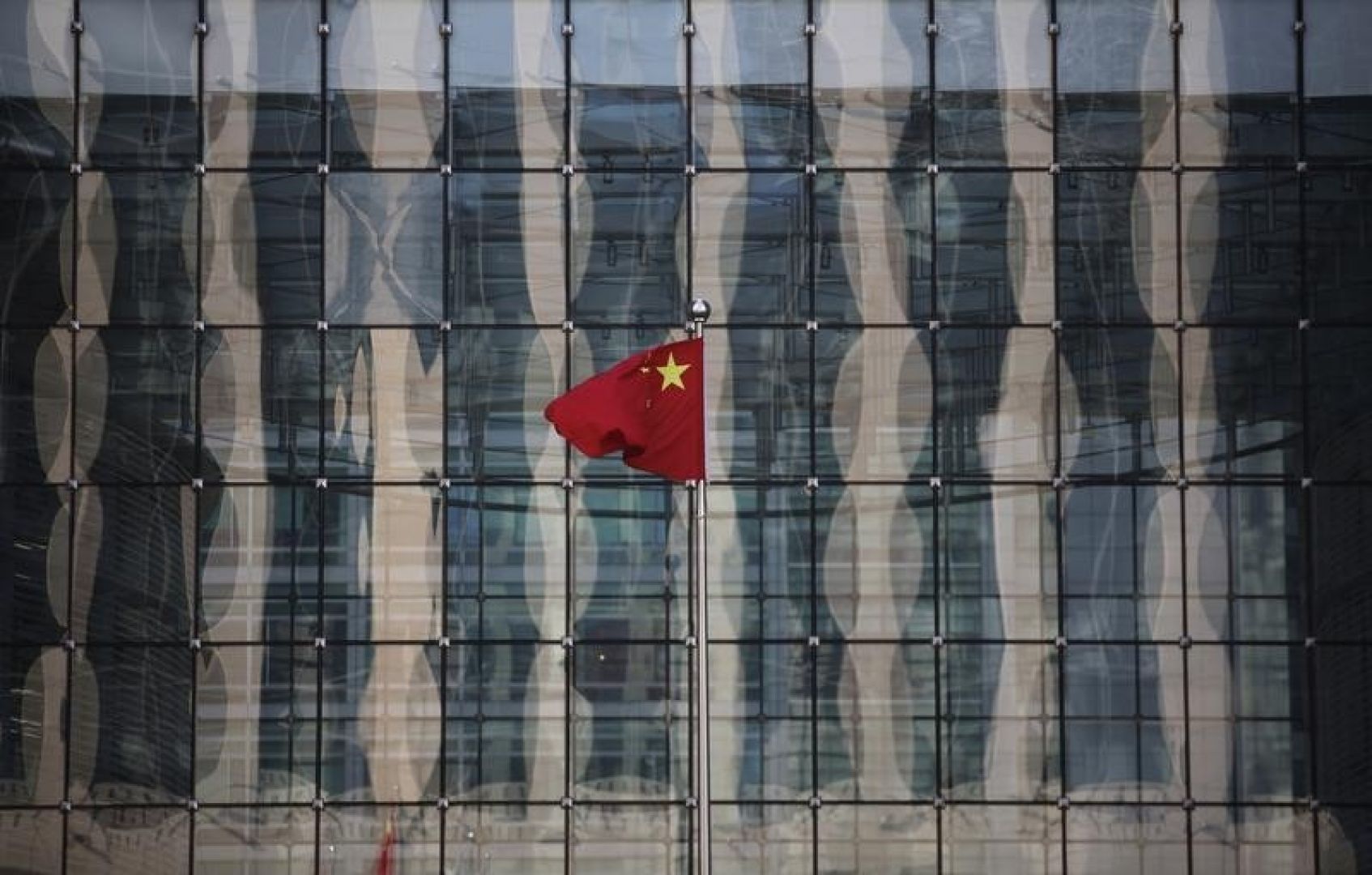

Image provided by today online.com