By Irene Chung

IRENE CHUNG reviews David Shambaugh’s new book China’s Future.

To professors teaching a survey course on China: assign David Shambaugh’s China’s Future and just call it a day. Reading Shambaugh’s short book on China’s future, I was immediately reminded of the extensive coursework on China available here at Yale—what Shambaugh calls the “Big Topic.” From courses like “China in World Politics” and “The Next China” to “China from Mao to Now,” Yale has its fair share of classes whose goal is the same as Shambaugh’s: to evaluate the state of affairs in China, to predict the country’s next developments, and to suggest global repercussions.

As a student of U.S.-China relations involved in the China “scene” on campus, I have taken many of these courses. And while reading Shambaugh’s book, I reflected on the many hours I have spent in the last three years of my college education typing away in lecture, writing policy memos, and debating these very topics in discussion sections. How did Shambaugh do in a few chapters what I have spent multiple course credits on? And who did it better?

Shambaugh, Professor of Political Science at George Washington University and Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institute, disagrees with many China scholars, including some at Yale, who are optimistic about China’s growth potential. Instead, he predicts a bleak future for the country, representing a recent shift to skepticism towards China’s continuous rise. Disagreeing with conventional wisdom, Shambaugh claims that China does not differ from other post-socialist countries whose economic modernization was tied to political democratization. He argues that China cannot continue its economic development without political and social liberalization, or becoming what Shambaugh calls an “inclusive state.” In order for China’s economy to bypass a certain development ceiling, Chinese institutions must be facilitative and social actors must enjoy greater autonomy.

Shambaugh begins by arguing that if the regime stays on its current course, economic modernization will halt and eventually ruin the Chinese Communist Party, a consequence of “trying to create a modern economy with a pre-modern political system.” To Shambaugh, the political and economic situation of any given country is independent of geopolitical influences, and, in the case of China, the evolution of its politics and economics will determine the country’s continued growth or collapse. Shambaugh corroborates his claims with both quantitative data and qualitative analysis, attempting to put China’s economy into global context.

But ultimately, Shambaugh lacks follow-through. His book is organized like a survey course on China, and offers breadth at the expense of convincing argument or analysis. While it provides a wide-ranging overview of the country’s current state of affairs, much like an introductory course syllabus, Shambaugh’s attempt to address every aspect of the Chinese economic and political situation dilutes the strength of his claim. As a result, instead of being comprehensive, he is reductive.

Internally, Shambaugh enumerates several pressing challenges facing China’s economy, from the lack of implementation of central policies to a volatile property market to the thriving “shadow banking” economy. Shambaugh offers numerous possible reforms for the Chinese economy, from stimulating personal spending to reforming state-owned enterprises, that seem impossible for the economic behemoth to achieve. Overwhelmed by the volume of things to fix and a lack of prioritization or substantiation, the reader feels that none of Shambaugh’s suggestions are weighty.

Externally, Shambaugh loves to pose grand questions about China’s international role that he cannot meaningfully respond to: What will be the nature of China’s future interactions with the world? How will the country’s external environment impact its internal situation? These are questions that Shambaugh promises to answer, but he quickly skims over crucial issues such as the relationship between China and South Asia in just a few paragraphs. He name-drops the One Belt, One Road initiative and the Asian Infrastructure Bank and never gives the reader a sense of how these position China on the world stage.

Shambaugh’s error lies in his ambition: he presents empirical evidence that spans nearly every facet of Chinese politics, society, and economics. In trying to cover so much ground, Shambaugh makes too many assumptions and oversimplifies complex issues. In fact, some parts of his arguments seem to be tautological, as Shambaugh assumes the main argument that he seeks to prove: that China cannot advance economically without political opening-up.

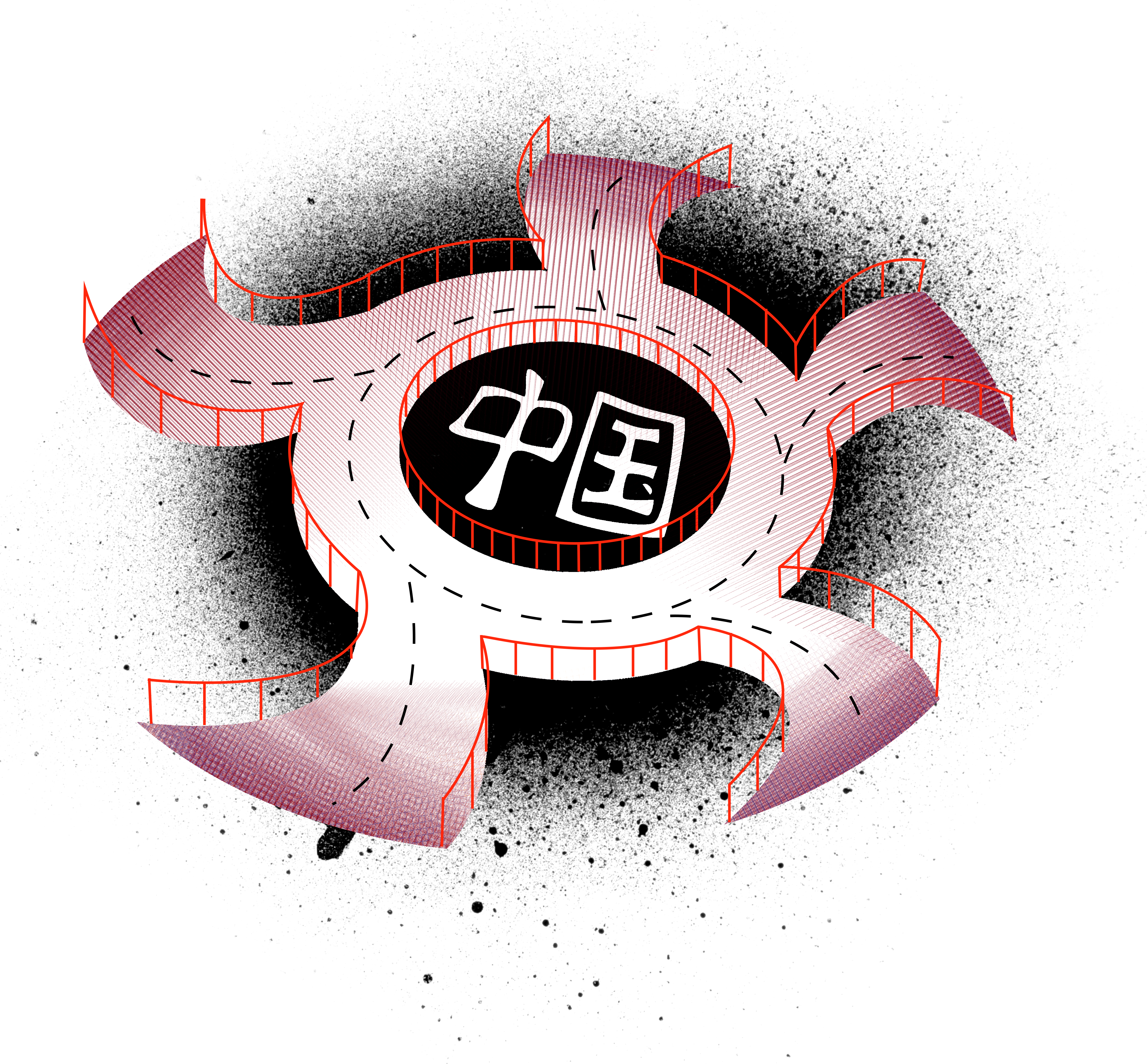

Attempting again to be comprehensive, when it comes to predicting changes for China, Shambaugh tries to touch on every possible scenario. He frames his discussion with four possibilities for political systems, from neo-totalitarianism to semi-democracy. Shambaugh compares China to a car approaching a roundabout: the car has four different exit options but does not know which to take. With such a range of possibilities, the reader is left puzzled at what exactly Shambaugh believes will occur—together, they span the entire gamut of possibility.

While this may be an appropriate approach for a classroom setting where the professor helps students form their own opinions, readers cannot help but feel unsatisfied with this laundry list. Shambaugh never eliminates any potential routes for China’s future. Instead, he skirts around concrete conclusions, hedging his assertions, and positing that each is “not a completely unfeasible scenario.”

David Shambaugh’s prosaic tone, quick assumptions, and hand-waving predictions create the illusory notion that he offers a well-formulated position on China. While his voice is a valuable one representing a growing cohort of pessimistic China watchers, I think the contents of this book are more appropriate for broad exposure to issues facing China than for gleaning any real conclusions. Professors often hope to keep their personal opinions out of the classroom to create an environment of neutrality. Shambaugh has succeeded in doing this. His book has a strong structure to be a survey course, but for me that is not fully satisfying: I want to come to a book’s final pages agreeing or disagreeing with the author. And to Shambaugh, all I can say is, “So what do you think?”

Irene is a senior at Yale College. Contact her at irene.chung@yale.edu.

Illustration // Catherine Yang

China’s Future

By David Shambaugh

Polity $18.95

189 pp.