JERRY FENG researches the tributary system of China over its millenia-long history and its evolution over time until the challenge of its order post-Opium War.

Much of how the world we know today operates has been formed as a result of Europe’s domination of world politics during their centuries of world colonization and imperialism. Following the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648, European nations committed to the idea of equality of sovereign states on the international stage and thus spread this idea over its vast colonial domains. However, for much of China’s millennia-long civilization and history, it has been the strongest centralized power that has comfortably exerted long-lasting influences across all of East and Southeast Asia and, arguably, their known world at the time. As the premier superpower of Asia for thousands of years, the Chinese civilization has managed to understand its relationships with surrounding political entities, create an institutional framework to solve conflicts and peacefully co-exist, and has operated successfully within that system of its own creation throughout its history. However, since China’s conflict-ridden exposure to the Western world in the early- to mid-19th century, it has continuously had its concept of world order challenged. In this paper, I seek to argue that the tributary system was largely a successful and flexible system up until the Opium War of 1839 and onwards. And, the gradual demise of China’s suzerain-vassal relationships shows that there was still a strong adherence to this world order by its participants despite the military superiority of the new order.

To begin with, the ‘tributary system’ as a concept used to describe the history of the ‘Chinese world order’ is actually only a recently coined term by John Fairbank, an American historian of China and US-China relations. The English words ‘tribute’ or ‘tributary’ are not actually the most encompassing or accurate way to really describe the system. In Classical Chinese — a form of literature used by the intelligentsia, upper elite, and government classes throughout China’s dynastic history — the word gong (貢), from which we derive the word ‘tribute’, actually has numerous meanings. The general idea is the act of giving gifts from an inferior to a superior position, whether that is from the emperor to Heaven, a court official to the emperor, or commoners to local leaders. This act of gift-giving is also reciprocated: Heaven brings prosperity and peace to the land, the emperor gives imperial titles to subordinates, and so on. Most importantly, however, there is no distinction between tribute given as a native from China and those given from outsiders.

This tributary system largely began during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 CE) and lasted all the way until the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). The basis for this worldview from the Chinese perspective comes from the idea that China is the “Middle Kingdom” (zhongguo in Mandarin) that rules ‘all under Heaven’, and thus was culturally superior to all other surrounding vassal states. Those outside of the vast Chinese cultural ‘cosmos’ were seen as ‘barbarians’ needing to be tamed. But this idea also has roots in the incredibly influential Confucianism, ideas of the ancient sage thinker Confucius, that could be understood as almost a state ideology for the vast majority of China’s dynastic rule. In Confucian thinking, hierarchy is simply the natural order of things: sons obey fathers, court officials obey the emperor, and it is expected that everyone plays their role faithfully. Additionally, this Confucian view of hierarchy is one based on “moral virtue” rather than on the “power of military force,” so emperors are expected to govern well just as a father should treat his son.

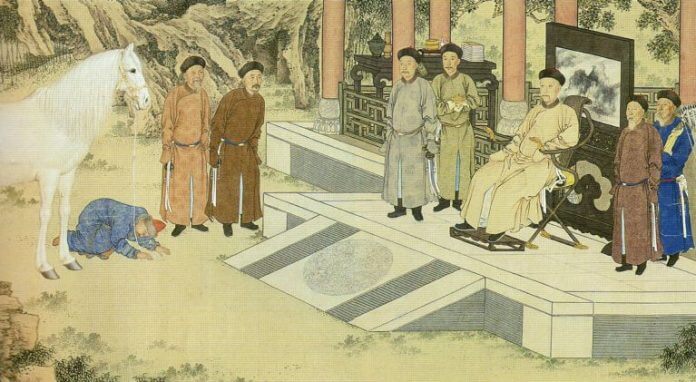

In addition to the moral view based on Confucian ethics, there was also a strong emphasis on ritual performance. When performing tribute, the tributary envoys would perform the full ‘Kow-tow’ — “kneeling three times, for a total of nine taps” — as a way to show their acceptance of inferior status and then proceed to present the gifts, often products such as food native to their own lands. In response to show the superior status of China in power and wealth, the emperor would also give silks and gold among other precious items that often exceeded the value of the tribute itself. This cultural universe based on Confucianism and Chinese culture would later become so ingrained in the Sino-spheric states of Vietnam, Korea, and, to some extent, Japan that they came to internalize this institutional framework of the tribute. For the most part, this system has largely led to a general peace in East Asia, so long as China was still the stable power in the region.

This tributary system — though seemingly a rigid hierarchical structure — is actually quite flexible, and states’ roles and relationships among states can quickly change to reflect a change in power dynamics. During the Han Dynasty and Tang Dynasty (618–907), it can be argued that there was roughly a power parity between the Han and Tang and their main adversaries. For the Han specifically, the biggest challengers to their rule were the nomadic tribes in the northern and western steppes, known as the Xiongnu. Though they viewed themselves as the superior, more civilized people, the Han still ended up conferring gifts onto the Xiongnu, often through showery and flattering terms as a strategic tactic to both show: 1) they were on relatively diplomatically equal terms, and 2) to ‘tame’ the barbarians as a way to maintain peace. For the Tang Dynasty, one powerful adversary was the massive Tibetan Kingdom to the west, and, one way the Tang showed relative diplomatic parity with the Kingdom was by agreeing to marriages between the Tang and the Tibetan royal families. As such, for both the Han and Tang Dynasties, the hierarchical structure was malleable, but they both worked within the framework of the tribute system, conferring tribute in the name of accepting parity and maintaining peace.

The Song Dynasty’s (960–1279) relationship with the Liao Dynasty also exhibited a level of power parity, where, following the Han and Tang examples, reciprocal tribute gifts and occasional military conflicts established a mutual understanding of diplomatic equality. But, the Song’s relationship with the Jurchen Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) was more evident of an asymmetrical relationship where, arguably, the power center was not Han China proper for the first time, but rather a perceived barbarian. Initially, following the rise of the Jin — the “direct forebears of the Manchus” — the Song made a military alliance to conquer the Liao in 1116, but the Jin quickly turned onto the Song, taking the portion of the Northern Song Dynasty. Though stronger than the Song militarily, repeated skirmishes still left the Southern Song able to fend itself off; the subsequent peace treaties that set the status quo were incredibly humiliating for the Song side, needing to pay 250,000 taels of silver annually to the Jin and accept inferior status. Despite this inferior status, the Southern Song was still able to flourish in its economic and literary developments. Many scholars would even argue that the Southern Song, specifically, was one of the most accomplished dynasties of China in cultural terms. As such, despite having created this international hierarchical system, the Chinese have found ways to work within the system to achieve prosperity, despite their perceived humiliating terms of agreement.

Regardless of the Song’s weaker position, which may seem to be a logical lure for countries seeking to escape the China-dominated world order, there seems to be an early adherence to the system. In 968, Vietnam, which had long been administered by China, declared independence; in 981, the Song Dynasty tried to reestablish control of Vietnam but failed. However, instead of completely breaking away from the system, the following Ly Dynasty (1010–1225) decided to reestablish tributary relations with the Song, signifying its refusal to completely deviate from the system.

Following closely in the early period of the Ming Dynasty (1360–1644), the Emperor decided to try and increase tributary presence as the main form of China’s foreign trade and thus launched numerous expeditions across Southeast Asia to India, the Arabian Peninsula, and the East African coast. Throughout this time, records showed that as many as forty states were visited, and most had sent back envoys with the Chinese fleet as acknowledgment of their tributary status. However, with time passing, it became clear that the tributes were hardly sustainable, and thus a renewed focus on private trade as tribute from vassal states began, opening up many of China’s southern and southeastern ports as “frontier zones” to receive tributary envoys. By the time the Qing Dynasty came to power, however, much of the tributary system was “abandoned” in favor of the private trading system, but records still showed that between 1762 and 1861, there were about 255 recorded tribute missions, an increase from 216 in between 1662 and 1761, with the cause being attributed to trade missions rather than solely tribute. Most states sent tribute on a regular basis, including some European nations with colonies in the area or trade relationships with the Chinese mainland. In particular, it notes that:

With perhaps a couple exceptions, Korea sent tribute every year steadily until 1874…Tribute from [Ryukyu] was recorded in some 70 years out of the 144 years from 1662 through 1805, that is on the average almost exactly as required by the statute. But in the next 54 years from 1806 to 1859, tribute from [Ryukyu] instead of being biennial was recorded 45 times, on the average in five out of every six years…Annam was recorded 45 times in the 200 years from 1662 to 1861, somewhat less than the average of one in four years, which agrees fairly well with the shifting regulations for [Vietnam].

Towards the end of the Ming and early Qing period, it became clear how ingrained this worldview was in the Sino-spheric world, particularly in Korea and Japan. During their struggle for supremacy, both the Ming and Manchus (later Qing) vied for influence and suzerainty in Korea; the Manchus invaded Korea in 1627 and 1636 with the subsequent peace accords demanding Korea shift its tributary status from the Ming to the Manchus. Initially, the Koreans had a policy of accommodation, but when asked to wage war against the Ming from the Manchus, the Korean King refused by saying that “[t]he Ming is a country like that of our own father to us…” and went further on by rejecting to pay the amount of tribute requested by the Manchus. From here, there is clear evidence of the deep roots of the Confucian way of thinking of the hierarchical relationship between Korea and the Ming Dynasty. Even the Japanese who were run by the Tokugawa Shogunate and were at war with the Ming just decades prior reached out to Korea after the first invasion offering their own military support. However, the response to the Manchus — and the officially-established Qing later on — was not entirely without precedent. Both the Koreans and Japanese saw the Manchus as barbarian-like, similar to the Mongols of the previous Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368); when the Ming Dynasty was first founded, Korea was almost immediately willing to shift allegiance from the Yuan to the Ming, a stark contrast with their relationship to the Manchus, and Japan refused to even recognize establish diplomatic ties with the Qing following the collapse of the Ming. While seemingly a superficial classification between ‘civilian’ and ‘barbarian’, this simple distinction had major political consequences for the early Qing hoping to establish governing legitimacy: the two other main loyal Sino-centric states either doubted or completely refused to acknowledge that the Qing truly had a claim to the ‘Mandate of Heaven’.

Once the Qing had established solid control of the heart of the Chinese civilization, they were faced again with the problem of a powerful neighbor, Russia. And, just like the Han and Tang did with their relatively co-equal adversaries, the Qing used similar tactics to try and pacify their new big northern neighbor. Different from all other previous ‘barbaric’ peoples outside of the Chinese heartland, Russia did not live under any prior knowledge or internalized assumption that the Chinese civilization was ‘all under Heaven’, nor that China was a superior civilization; but, the pre-eminent Qing Emperor Kangxi wished to uphold this international system he fought for. Throughout the mid- to late-1600s, there were numerous skirmishes between Russian Cossacks and the Qing in Far East Siberia and Manchuria, but neither side was willing to risk a major clash. Ultimately in 1689 and 1728, the Treaty of Nerchinsk and Kyakhta, respectively, settled territorial boundaries on relatively equal terms (though it could be argued the Manchus certainly had the upper hand), and this status quo lasted until the 1850s. On the Qing side, the question of tribute became more an issue of pragmatism for strategic reasons; on the Russian side, there was a greater focus on commerce in exchange for peace. Communications between Peking and St. Petersburg happened at the level of secondary officials, thus avoiding the issue of needing to address each other’s czar or emperor as an ‘equal’ or ‘superior.’ Additionally, Russian trade caravans were recorded by the Qing to be for tribute purposes but never required the merchants to perform rituals or partake in ceremonial kowtows, thus showing the pragmatic part of the equal relationship between the two nations. Russia was also content with having an unofficial presence through its trade caravans to China. This example shows that even with a newcomer into the Chinese world order, the tactics used for millennia prior against the Xiongnu and other tribes were largely successful through their malleability.

The issues that came to challenge the Chinese world order largely came from maritime European powers, who seized vassal state after vassal state away from China as colonies for themselves. Losing the Opium War in 1842 followed by successive losses of wars against the British and French in 1860 and throughout the late 1800s revealed Qing China to be a paper tiger. Aside from just the military and geopolitical defeat, the treaties that granted foreign powers commercial privileges, territorial concessions, and extraterritorial rights to foreigners in China were a direct objection to the Chinese world order. As a result of these changes, all the privileges that originated from the tributary relationship were obtained through the treaties, rendering the tribute system irrelevant. Following increasing European presence in South and Southeast Asia, the Chinese world order’s existence was put to the final test with its remaining loyal vassal states, Vietnam, Korea, and the Ryukyu Islands. During the Meiji Restoration, Japan had broken away from the order and sought to establish its own hegemony among the European nations.

In 1876, Japan and Korea signed an agreement that completely ignored Chinese suzerainty in Korea. Later, the United States also signed its commercial treaty with Korea, but, even with the Chinese Viceroy (Foreign Minister in practice) Li Hung-chang’s attempts at swaying the decision in favor of China, Li was unable to get the United States to recognize the suzerain-vassal status between China and Korea. Not long after in 1879, China also lost its suzerainty status over the Ryukyu Islands over to Japan as well. Adding on to that, Li tried hard to hold onto its suzerainty status over Vietnam, but the ensuing Sino-French War (1883–1885), despite a near Qing victory, solidified French suzerainty over the region instead. And, following this string of failures, Japanese Foreign Minister Ito Hirobumi managed to conclude an agreement with Li Hung-chang for a “joint protectorate” over Korea, elevating the status of Japan as a diplomatic equal to the Qing Dynasty. Finally, the First Sino-Japanese War nailed China’s position as the inferior into the coffin and officially displaced China as the suzerain; the resulting Treaty of Shimonoseki discussed conditions very similar to the type of actions vassals take when sending tributary envoys to the suzerain.

For the most part, China was coerced into accepting the way the Western world worked, such as the exchange of embassies and permanent ambassadors in respective capitals and adopting the idea that all sovereign nations were nominally ‘equal’ in the international system. However, the reciprocal exchange also happened as many Western nations still played the Chinese world order ‘game’. In Memoirs of Li Hung-chang, Li writes about his Euro-America State Tour, and, in particular, the flowery language and performative measures that the Russians take to maintain positive relationships with him. He says:

“The Russians have long tried to impress me with the idea that they hold me in the highest esteem. Perhaps they do. Anyway they may have their motives for all this. And I have no doubt they have; but I could tell them that my country’s interests are above all other considerations…the Czar can hope to gain nothing by flattering me with honours or preferences.”

In addition to the Russians, the Americans also took certain note of particular wording or phrasing that may be of liking to the Chinese. During Li’s tour of the United States, his main point of contact was with US Army Major General Thomas Howard Ruger. In a letter to Yang Yu, the “Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor of China,” Thomas Ruger signed off the letter as “[y]our obedient servant,” which is highly reminiscent of the tone that inferiors use when talking to superiors; but, in this case, Yang and Ruger should be on relatively equal footing. So, it appears that Western nations like Russia and the United States have also adapted some of their ways to tactics used by the Chinese in the past.

Influential theorists of the international system often describe the world order as one akin to anarchy. In The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, John Mearsheimer lays out five major assumptions about the international system, the first one being that the international system is “anarchic by nature.” In Hierarchy in International Relations, David Lake argues that the world system is indeed anarchic, but rather “a mixed society with pockets of relative anarchy in which self-help remains the rule and pockets of relative hierarchy in which a measure of authority, peace, and free trade prevail.” The areas where there is no anarchy are rather centered on the relationship between “dominant” countries and their “subordinate” states. What David Lake argues about the modern world order really could just be how the Chinese have already operated their own ‘tributary system’ world order for millennia: one major dominant “hegemon” (or suzerain) with “imperial supplicants” (vassal states) that perform “symbolic obeisance” (tributary missions).

Throughout the millennia-long history of the Chinese tributary system, it has shown remarkable flexibility and success in cultivating a relatively peaceful relationship with those who partake in it. In the Han, Tang, and Qing dynasties, pragmatism in the need for prioritizing strategic interests made the hierarchical worldview malleable to allow for equality among certain states, conferring tribute to symbolize that parity, including to the ‘barbaric’ states. But, even in times when it seemed China was the inferior, in the case of the Song Dynasty relative to the Liao and Jin, China still made the most out of their lesser position and thrived, leading to one of the most culturally accomplished dynasties in Chinese history. From the cases of states that are loyal to the Chinese world order, such as the case with Vietnam, Korea, and Japan (Japan before its Meiji Restoration), it is clear that many benefitted enough from the system to uphold it, whether that came in the form of resuming tributary relations or refusing to recognize a barbarian as legitimate rulers of China. Despite material challenges post-Opium War that led to the demise of China and its relations with its vassal states, many Western nations still didn’t completely shun the Chinese world order. Nations like Russia and the USA showed signs that they learned how to communicate with China to bolster their own standing with the Qing, except in a somewhat ironic way where power dynamics are flipped. Ultimately, the Chinese world order or Chinese tributary system was one remarkable feat that lasted for two millennia and has contributed to relative peace among those most loyal to the system. Despite being cast aside following the weakening of the Qing Dynasty, this system’s relevance to today’s world is still strong, especially in an ever-increasingly multipolar world. Perhaps the Chinese were right in that hierarchical relationships are the natural order of things, but we just need to find the right balance in asymmetrical relationships.

Jerry Feng is an undergraduate student at Yale College studying History and Global Affairs. Jerry can be reached at jerry.feng@yale.edu.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Douglas, Robert K. Li Hungchang. New York: F. Warne, 1895. Pdf. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b4315967.

“Exit Li Lung Chang.” Beira Post, September 28, 1898, 2. Nineteenth Century Collections Online (accessed May 6, 2024). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/TFVIOH027727592/NCCO?u=29002&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=38a677c5.

Little, Archibald. Li Hung Chang: His Life and Times. London: Cassell, 1903. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t77s8871s.

Mannix, William Francis. Memoirs of Li Hung Chang. Boston, New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1913. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/13022226/.

M. “Li Hung Chang.” Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. XLIX, 1918, pp. 179+. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/ONGAIA229412990/NCCO?u=29002&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=5e184031.

“The Crisis in the North: Yung Lu Again the Hand of Yung Lu Yu Yin Un the Russo-Chinese Treaty a Guilty Conscience ‘Tit for Tat.’ The Crisis in Hsian China, Russia, and the Towers a Series Consultation Chang Pei-Lun Amongst the Telegrams.” 1901. The North – China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette (1870-1941), Mar 20, 547. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/crisis-north/docview/1369469962/se-2.

“The Far Eastern Question: Li Hung-Chang’s Mission and its Sequel.” 1897. The North – China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette (1870-1941), Mar 19, 499. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/far-eastern-question/docview/1369457751/se-2.

“The Problem of Manchuria: A Secret Treaty by an Admirer of Li Hung-Chang.” 1910. The North – China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette (1870-1941), Mar 11, 536. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/problem-manchuria/docview/1369520062/se-2.

Thomas Howard Ruger Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Secondary Sources

Carty, Anthony, and Janne Nijman (eds), Morality and Responsibility of Rulers: European and Chinese Origins of a Rule of Law as Justice for World Order (Oxford, 2018; online edn, Oxford Academic, 19 Apr. 2018), 360–433. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199670055.001.0001.

Fairbank, J. K. “Tributary Trade and China’s Relations with the West.” The Far Eastern Quarterly 1, no. 2 (1942): 129–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2049617.

Hevia, James L. “Tribute, Asymmetry, and Imperial Formations: Rethinking Relations of Power in East Asia.” The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 16, no. 1/2 (2009): 69–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23613240.

Lake, David A. Hierarchy in International Relations. Cornell University Press, 2009. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt7z79w.

Larsen, Kirk W. “Comforting Fictions: The Tribute System, the Westphalian Order, and Sino-Korean Relations.” Journal of East Asian Studies 13, no. 2 (2013): 233–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23418776.

Lee, Ji-Young. China’s Hegemony: Four Hundred Years of East Asian Domination. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017.

https://doi.org/10.7312/columbia/9780231179744.001.0001

Lin, Hsiao-Ting. “The Tributary System in China’s Historical Imagination: China and Hunza, ca. 1760-1960.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 19, no. 4 (2009): 489–507. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27756100.

Mancall, Mark. “The Persistence of Tradition in Chinese Foreign Policy.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 349 (1963): 14–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1035694.

Mearsheimer, John J. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton, 2014.

Munez, E.. “Tributary System.” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 18, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/tributary-system.

Perdue, Peter C. “China and Other Colonial Empires.” The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 16, no. 1/2 (2009): 85–103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23613241.

Perdue, Peter C. “Boundaries and Trade in the Early Modern World: Negotiations at Nerchinsk and Beijing.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 43, no. 3 (2010): 341–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25642205.

Rawlinson, J. Lang. “Li Hongzhang.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 21, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Li-Hongzhang.

Selbitschka, Armin. “Early Chinese Diplomacy: ‘Realpolitik’ versus the So-Called Tributary System.” Asia Major 28, no. 1 (2015): 61–114. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44742487.

Snow, Philip. China and Russia: Four Centuries of Conflict and Concord. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023

Wang, Yuan-kang. “Explaining the Tribute System: Power, Confucianism, and War in Medieval East Asia.” Journal of East Asian Studies 13, no. 2 (2013): 207–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23418775.

Westad, Odd Arne. Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750. New York, New York: Basic Books, 2012. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.yale.idm.oclc.org/lib/yale-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3029400

Zhang, Yongjin. “System, Empire and State in Chinese International Relations.” Review of International Studies 27 (2001): 43–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45299504.

Wang, Yuan-kang. “Explaining the Tribute System: Power, Confucianism, and War in Medieval East Asia.” Journal of East Asian Studies 13, no. 2 (2013): 207–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23418775.