VICTORIA TANG explores how China’s often overlooked strategy during the cold war, leveraging the superpower standoff to assert radical independence, export Maoism, and rebrand itself as a revolutionary leader of the developing world. Far from being a Soviet satellite or regional footnote, the PRC carved its own “third path”—diverging from the USSR, wooing the U.S., and rallying the Global South under the banner of postcolonial revolution. In doing so, it laid the groundwork for its modern-day geopolitical influence in the Global South.

“There is great disorder under heaven; the situation is excellent.”

— Mao Zedong, 1957

In the aftermath of World War II, the global order was fundamentally reshaped by the emergence of two superpowers locked in ideological opposition: the capitalist United States and the communist Soviet Union. This confrontation, known as the Cold War (1947-91), waged not through direct military confrontation between the two giants, but rather through a series of proxy wars, political alliances, intelligence operations, economic development strategies, and cultural influence campaigns. From the battlefields of Korea and Vietnam and the diplomatic arenas of the United Nations to propaganda broadcasts transmitted across airwaves, the Cold War permeated all aspects of international relations. At its core was the struggle to define the future of global governance, economic systems, and ideological dominance in the wake of decolonization and the collapse of European empires. Most historical narratives cast the Cold War as a binary conflict between solely the Soviet Union and the United States. However, this portrayal overlooks the complex role of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which emerged as a revolutionary state in 1949 after decades of civil war and anti-colonial struggle. Under Mao Zedong’s leadership, China initially aligned itself closely with the Soviet Union under the banner of Marxism-Leninism, receiving economic aid, military assistance, and ideological direction. The two nations presented a united front in the early 1950s, particularly during the Korean War, in which Chinese troops fought alongside North Korean and Soviet-supported forces against a U.S.-led coalition. However, this unity proved fragile. By the late 1950s, ideological tensions and strategic differences began to rupture the alliance, setting China on a unique Cold War trajectory. While China is often portrayed as a subordinate Cold War actor—either as a Soviet satellite or a reactive regional force—it actively leveraged the global conflict to assert ideological autonomy, claim postcolonial legitimacy, and position itself as a leader of the developing world, pursuing a self-defined revolutionary strategy that challenged both Soviet control and Western dominance. China’s break from the Soviet Union, its postcolonial rhetoric and diplomacy, and its efforts to cultivate Third World alliances all reveal a Cold War strategy rooted in self-defined global power, not dependency.

Part I: Ideological Independence—Diverging from the Role Model of the Soviet Union

China’s unique path during the Cold War first became visible after its break from the Soviet Union during the 1950s and 1960s. This break was not merely a geopolitical rift but a calculated assertion of ideological independence that allowed China to redefine what it meant to be a revolutionary power on its own terms. Initially bound by the 1950 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Mutual Admiration for Marxism-Leninism, the alliance quickly fractured over disagreements about the direction of global communism. Chinese Chairman Mao Zedong accused Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev of betraying revolutionary ideals through “revisionism” and capitulation to Western imperialism. In his 1964 statement “On Khrushchev’s Phony Communism,” Mao denounced Soviet peaceful coexistence as a counterrevolutionary stance, arguing instead for permanent class struggle and mass mobilization. The ideological divergence had significant implications beyond mere rhetoric:Mao viewed revolution not as a single historical moment but as a continuous and evolving struggle that required constant ideological vigilance.

Mao’s revolutionary vision diverged sharply from the more cautious and bureaucratic communism of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. Whereas Khrushchev pursued peaceful coexistence with the West and centralized economic planning, Mao advocated for perpetual revolution, self-reliance, and mass mobilization rooted in rural peasant communities.

These ideological tensions culminated in the 1963 document Proposal Concerning the General Line of the International Communist Movement, a letter from the Chinese Communist Party to the Soviet leadership written at the height of the Sino-Soviet split. The Chinese sharply reject what they viewed as the Soviet Union’s betrayal of revolutionary principles. The Chinese argued that “if the general line of the international communist movement is one-sidedly reduced to ‘peaceful coexistence,’ ‘peaceful competition,’ and ‘peaceful transition,’ this is to violate the revolutionary principles of the 1957 Declaration and the 1960 Statement.” This divergence triggered the Sino-Soviet split, a pivotal moment that shattered the unity of the international communist movement and forced global powers to recalibrate their diplomatic and strategic alignments. China’s subsequent ideological and strategic realignment had profound implications. It not only fragmented the international communist bloc but also challenged the very structure of the Cold War, which had previously been understood as a binary struggle between two superpowers.

This conviction led to domestic campaigns such as the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962), which attempted to catapult China into industrial modernity through collective farming and backyard steel production. Despite its catastrophic human toll—an estimated 30 million deaths from famine—the campaign revealed the depth of Mao’s commitment to revolutionary transformation over technocratic governance. Mao’s subsequent launch of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) further underscored China’s ideological extremism. The campaign, aimed at purging remnants of bourgeois values and capitalist thought, mobilized millions of young Red Guards to attack perceived “enemies” of the revolution. The chaos destabilized institutions, decimated intellectual life, and isolated China diplomatically. However, it also solidified Maoist China’s distinct identity as a revolutionary society committed to ideological purity above all else.

Historians such as Lorenz Lüthi argue that this split allowed China to claim moral and ideological leadership over the global communist movement. By promoting a militant, anti-revisionist stance, China inspired numerous revolutionary movements worldwide, from the Shining Path in Peru to guerrilla insurgencies in Southeast Asia. The Sino-Soviet split thus transformed China from a subordinate in the communist world to an autonomous ideological force that redefined what communism meant for the postcolonial world. Mao’s emphasis on ideological purity over technocratic efficiency positioned China not only as a geopolitical actor but as a symbolic champion of radical transformation.

Part II: Postcolonial Power Assertion— Leveraging the Two Superpowers

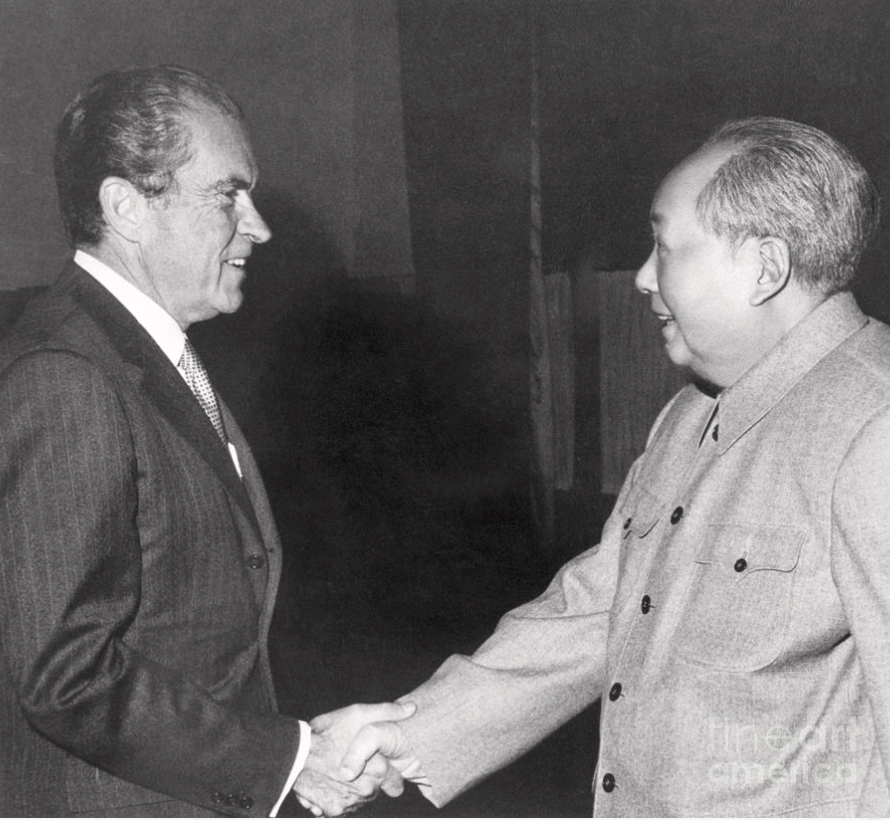

China’s engagement with revolutionary movements in the Global South, its support for anti-imperialist causes, and its eventual rapprochement with the United States added further complexity to the global order. Having asserted itself as an autonomous actor distinct from both the U.S. and the Soviet Union, China began translating its ideological independence into strategic diplomacy. As tensions with the Soviet Union escalated—including deadly border clashes in 1969 along the Ussuri River—China recalibrated its foreign policy and sought to shift the global balance of power through a bold new strategy: rapprochement with the United States. The result was one of the most unexpected realignments of the Cold War. In 1972, President Richard Nixon visited Beijing, signaling a dramatic shift in U.S.–China relations and opening the door to diplomatic normalization. This diplomatic pivot marked a departure from the rigid bipolarity of the early Cold War years. For China, rapprochement with the United States was less about ideological compromise than strategic calculation. As acknowledged by the United States in the Joint Statement Following Discussions With Leaders of the People’s Republic of China issued in 1972 in Shanghai, “There are essential differences between China and the United States in their social systems and foreign policies. However, the two sides agreed that countries, regardless of their social systems, should conduct their relations on the principles of respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states… and peaceful coexistence.” By breaking the isolation imposed by both the Soviet bloc and the Western alliance, China gained room to maneuver internationally and domestically. This visit enabled China to gain admission to the United Nations as the legitimate representative of China in 1971, replacing the Republic of China on Taiwan, and to begin trade and technological exchanges with Western countries.

The transcripts of Nixon’s meetings with Mao and Premier Zhou Enlai reveal a pragmatic China eager to counterbalance Soviet power. Nixon, too, saw China as a strategic lever against the USSR. Margaret MacMillan, in “Nixon and Mao,” argues that China’s triangular diplomacy “exploited the fissures in the Cold War order,” effectively undermining the notion that the world was locked in a rigid East-West binary. This maneuvering transformed the Cold War into a tripolar contest in which China exercised disproportionate influence despite its relative economic and military weakness. Furthermore, Henry Kissinger’s memoir, On China, reveals the depth of Chinese strategic thinking. Mao and Zhou saw engagement with the United States not as a betrayal of communism but as a necessary act of self-preservation and long-term positioning. China’s leaders recognized that survival required flexibility and engagement with global systems. This realignment enabled China to open its economy under Deng Xiaoping, pursue modernization through the Four Modernizations, and chart a path distinct from Soviet-style stagnation.

China’s role in reshaping Cold War alignments proved the limitations of the bipolar framework. It forced both superpowers to recalibrate their strategies, intensified Soviet insecurity, and opened new spaces for smaller states to pursue non-aligned policies.

Part III: Leader in the Third World–Rising From Surviving Tactic to New Century Ambition

Finally, in addition to ideological and diplomatic shifts, China positioned itself as a leader of the Global South by championing anti-imperialism as a role model and supporting revolutionary solidarity in other countries, actively cultivating alliances across the Global South to construct a vision of Cold War power that challenged the bipolar dominance of the United States and the USSR. At the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia, China joined leaders from newly independent Asian and African nations in advocating for a third way between Western capitalism and Soviet communism. Premier Zhou Enlai emphasized racial equality, national sovereignty, and shared struggle against colonial oppression—principles that resonated deeply across decolonizing nations. By framing itself as a fellow victim of imperialism, China strategically employed its postcolonial identity to build legitimacy with newly independent nations, positioning itself as a moral alternative to both Western capitalism and Soviet hegemony.

China’s commitment to postcolonial solidarity was not just rhetorical. It backed these ideals with material support, aiding anti-colonial movements in Vietnam, Algeria, Tanzania, Zambia, and beyond. Maoist ideology, emphasizing rural guerrilla warfare, protracted people’s war, and self-reliance, proved especially appealing to revolutionaries in agrarian societies facing entrenched colonial structures. China also provided weapons, military training, and ideological guidance to movements such as the Viet Cong in Vietnam, Frelimo in Mozambique, and Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) in Zimbabwe. Unlike the Soviets, who often worked through established political parties and governments, China focused on grassroots mobilization and direct revolutionary action. China’s willingness to bypass traditional diplomatic channels allowed it to cultivate relationships with non-state actors and position itself as a more authentic voice of liberation. The construction of the TAZARA Railway in East Africa, linking Tanzania to Zambia, served as both a material and symbolic gesture of China’s solidarity with anti-colonial governments. These relationships were not just strategic but transformational. China’s moral authority as a fellow postcolonial nation, combined with its ideological commitment to anti-imperialism, allowed it to forge enduring diplomatic and economic partnerships. These Cold War-era networks laid the foundation for China’s later global initiatives, including the Belt and Road Initiative. The echoes of Maoist solidarity can still be heard in China’s contemporary appeal to the developing world.

In conclusion, China’s Cold War trajectory reveals it to be a far more dynamic and autonomous actor than conventional narratives suggest. By severing ties with the USSR, strategically engaging with the United States, and positioning itself as a revolutionary leader of the postcolonial world, China redefined what it meant to be a communist power in a divided world. These moves not only fractured the Cold War’s ideological dichotomy but also allowed China to lay the foundation for its contemporary global influence in places like Africa and Latin America. The deeper significance of China’s Cold War path lies in its transformation from a Soviet apprentice to an independent revolutionary force and strategic global player. In asserting its ideological autonomy, redefining diplomacy through triangular engagement, and cultivating solidarity with the Global South, China reshaped the Cold War’s ideological battlefield and redrew the map of global power. Today, its legacy continues to influence global alignments, particularly in the Global South, where China’s Cold War role as anti-imperialist ally has evolved into a twenty-first-century model of soft power and economic expansion—evident in large-scale infrastructure initiatives like the Belt and Road projects in Africa, investment in Latin American energy sectors, and the proliferation of Chinese-backed development loans across Southeast Asia. At the 2025 BRICS Summit, China spearheaded the expansion of the bloc to include nations like Egypt, Iran, and Indonesia, reconfiguring it as a broader coalition of the Global South. Through initiatives like BRICS Pay and its push for de-dollarization, China is not only challenging Western financial dominance but also reviving its Mao-era vision of an alternative global order—one rooted in sovereignty, non-alignment, and developmental solidarity among postcolonial states. China’s partnerships with nations across Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia—often grounded in infrastructure investment and calls for “true multilateralism”—demonstrate its ambition to shape a multipolar world order on its own terms. Understanding China’s Cold War strategy is therefore essential not only to understanding the Cold War itself, but to grasping the roots of the global order that followed.

In 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed—but by then, China had already grown into a leading developing country, and in the next 30 years became the world’s second largest economy with substantial global influence. If China had remained a subordinate “child” state to the Soviet Union since the 1950s, like Vietnam or North Korea, it would not be able to challenge the United States in trade, technology, or diplomatic impact; neither would there be the U.S.–China trade war, race for dominance in the Middle East and Africa, and rivalry to reshape the twenty-first century world order that is witnessed currently. The world today—defined by great power competition and geopolitical realignment—can be best understood by looking back seventy years to the strategic choices China made in the aftermath of World War II. Had China not chosen this third path and unleashed the “disorder under heaven,” today’s global landscape would look significantly different.

Victoria Tang is a junior at Choate Rosemary Hall in Wallingford, Connecticut. She has a deep personal investment in the intersection and bridging of China and the US. She is especially interested in East Asian Studies, history, sociology, and has conducted field research in rural China. Her work has been recognized by The Concord Review and the Scholastic Writing Contest. She can be reached at victoriatang0518@vip.163.com.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Bandung Conference (Asian-African Conference), 1955.” history.state.gov. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/bandung-conf.

Chen, Jian. Mao’s China and the Cold War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

“China, Soviet Union: Treaty of Friendship and Alliance,” The American Journal of International Law 40, no. 2 (1946): 20], https://doi.org/10.2307/2213813.

Friedman, Jeremy. Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition for the Third World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Gleijeses, Piero. Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Kissinger, Henry. On China. New York: Penguin Press, 2011.

Lüthi, Lorenz M. The Sino-Soviet Split: Cold War in the Communist World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

MacMillan, Margaret. Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World. New York: Random House, 2007.

Mao, Zedong. “On Khrushchev’s Phony Communism and Its Historical Lessons for the World.” July 14, 1964. In Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Vol. V, 411–31. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1977.Mcbride, James, ed. “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative.” Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative.