Xiaoyu Xia and Sophia Ng reflect on contemporary Chinese literature.

In reality, Mo Yan is not the first Nobel Laureate in Literature from China. Thirteen years ago, another Chinese author, Gao Xingjian, had also received the honor. However, the sensitive political status of Gao, who left for France in 1998, did not sit quite well with the Chinese government’s policies on art and literature. The China Writers’ Association released strong criticisms of Gao, which read as near opposites of the celebratory treatment Mo Yan had received.

That Mo Yan was Vice-Chairman of the China Writers’ Association at the time of his award prompted some criticism from the Western media, which charged his writings with complicity in the assimilation between literature and the Chinese Communist Party. Mo Yan’s works are certainly not simple repetitions or calls of support for the CCP’s policies and ideologies. In his works, one can find a deep compassion and colorful depictions of his hometown and land. More importantly, Mo Yan remains critical and sensitive to the historical trauma of modern China and its painful current transition towards modernity.

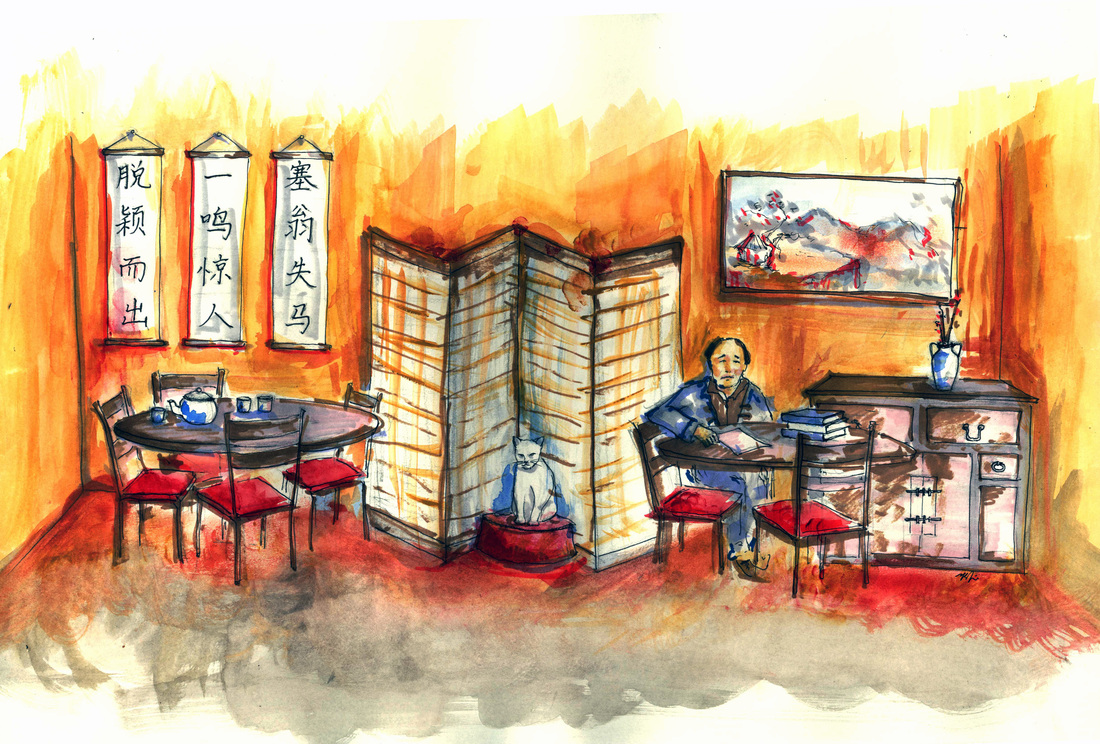

Besides Mo Yan, many other contemporary Chinese authors have also written about a politically troubled China. A representative example would be Jia Pingwa’s famed Ancient Furnace (《古炉》 Gu Lu). The Ancient Furnace is a novel more than 600,000-word long that depicts the biggest trauma that China has faced in the second half of the last century: the Cultural Revolution. Jia does not write about politics between the top government officials, nor did he write about the extreme cruelty or violence of the people. On the contrary, Jia writes from the perspective of an abandoned kid who is intellectually disabled, observing how the commoners found the strength to live on, amidst the era’s great trauma. The closeness of village life with mother nature seems to subtly comfort and soothe all the turmoil and bloodshed. A strong will to live resides within “ancient China,” and this very same China would still continue to thrive, despite facing any forms of disaster or humiliation.

These are just two of many novels which speak to the long-lying tensions in Chinese history, not least between the political center and the commoners. The concept of a “contemporary China,” let alone “contemporary Chinese literature” is complicated because of a certain inseparability from the more distant and traditional “ancient China.” For example, Pai Hsien-yong’s stream of consciousness novel Wandering in the Garden, Waking from a Dream is named after a traditional Kun opera. Pai’s novel of war and separation overlaps with the love story of Du Liniang in ancient China, and the author’s personal nostalgia. Another author, Luo Yijun, also intertwines the past and present in his novel, Hotel Xixia. Luo chose to reflect his thoughts on the past 60 years of political history through a novel that was set in a short-lived dynasty in ancient China. The past and the present are superimposed, and their relationship does not demonstrate a clear-cut distinction or continuum.

Both Pai Hsien-yung and Luo Yijun are from Taiwan. For a long period of time, the impression in China was that Chinese literature only includes literary works from mainland China. In recent years, there has been a push to redefine and broaden the definition of Chinese literature, with concepts like sinophone literature and overseas Chinese literature becoming hot discussion topics. Contemporary Chinese literature is less and less bound by a geographical concept, richer and deeper in terms of history, and much more multi-faceted in terms of language and ideologies.

Contemporary Chinese literature, in many respects, can be organized by whether it focuses on the present, future, or the past. For students majoring in Chinese literature in mainland China, the phrase “literature of the wounded” is a common point of discussion. This “wounded” literature is filled with testimonies and critiques of the Cultural Revolution and reflects upon the evils that the authors or fellow peers bore witness or committed.

How does the “literature of the wounded” reflect and critique upon the political mistakes of the previous era, and how then does the beginnings of such literature-led reflections shape and change the politics and ideologies of the present? Specific authors such as Mo Yan, Jia Pingwa, Yan Lianke, Yu Hua, and Su Tong all belong to the literary period of the “literature of the wounded.” Those living in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau, and other Chinese living overseas also have their own political ideologies and stories. While the “literature of the wounded’ in mainland China uses the Cultural Revolution as its mirror, most overseas Chinese writers continuously return to stories related to ancient China to fill in the historical gaps left behind by the trauma.

Even futuristic Chinese literature is unmistakably in conversation with China’s past, written with a sense of hope that the hold of the past may at last begin to loosen. Science-fiction and faith make frequent appearances in this body of literature. Liu Cixin’s magnificent Three-Body Trilogy (《三体》San Ti), is an apocalyptic fiction that confronts the destruction of the world and collapse of all civilizations. Yet, Liu leaves open a possibility for the revival of faith and love in the future of China after post-modernism.

Still, the Cultural Revolution cannot be fully shaken off. In another short story written by Liu Cixin, The Rural Teacher, (《乡村教师》 Xiang Cun Jiao Shi), he tells a tale of a village teacher who is determined to teach the children about the basics of Newton’s three laws of motion even as he nears his deathbed. Faced with a group of children who are unable to continue schooling, and have nothing but farming and poverty to look forward to in their lives, the village teacher’s efforts are almost entirely futile and meaningless. Yet these seemingly hopeless struggles are what help save the world from destruction. Some interpret Liu Cixin’s writings as overly sci-fi and idealistic, but others feel that in the desperate, irrational, and crazy era of the Cultural Revolution, it is only writers who held on dearly to their beliefs in education, knowledge, and that immovable faith in the future, who managed to save their humanity.

An author whose view on humanity vastly differs from Liu is Han Song. Han’s futuristic novels are similarly written in dystopia while his experiences as a reporter provide him with a deeper and more comprehensive view of China’s reality. Han’s latest work, Subway (《地铁》Di Tie), is a reflection of the alienation of technology. In the novel, the subway is a living hell in the realm of humans. The subway tunnels bring to mind Yan Lianke’s similar metaphor of tunnels in war as a living hell. Both are undoubtedly iconic items of two different eras in China, and the transition from underground tunnels to subways seems to hint to the reader that China has descended into yet another living tragedy, be it war, the Cultural Revolution, or cold materialism.

Despite the weight of the past and an uncertain future, contemporary Chinese literature does not neglect the daily rhythms of how we eat, pray, and love. For those born in China during the 90s, “daily life” holds a special meaning. The China of the 1990’s rapidly turned towards materialism and mercantilism. The increasing focus on “daily life” reflects the atomization of the individual human being under the pressure of capitalism and weakened societal links.

Ha Jin, a Chinese author who has lived in the US for near 30 years, has won several top literary prizes for his English works. In his speech, “The Individual and Literature” (《个人与文学》 Ge Ren Yu Wen Xue), he remarks that, “when I first began to write, I was always looking to be the representative voice of a specific group of people. But I later realized that you can represent no one but yourself. To write what touches your own soul – that is the most individualistic, and yet also the most universal.”

For a reviewer of Chinese literature for Western audiences, there is a sense of helplessness that the general reader might not be genuinely concerned about contemporary Chinese literature, but holds a greater interest in contemporary China instead. When Chinese-American author Amy Tan spoke at the International Shanghai Literary Festival in 2012, a participant mentioned that some Western readers had taken the representations of China in her book as the real China today, just like how people form oversimplified impressions of China through movies such as Disney’s Mulan or Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. None of these, of course, speaks to the real China.

How else does one recount the story of China? Is it a China that has surged in economic progress and seeking to move towards peaceful development, as shown during the Beijing Olympics? Or is it a China filled with corruption, high-speed train collisions, and earthquakes, a country with a high GDP but low standards of living and happiness index? It is true that all the stories reflect the reality in China, but they are only different parts of the full story. In other words, individually, they do not reflect a far more objective or comprehensive view of China than what you would expect through Western movies.

The “real” China is constructed through varied narratives and contains multiple images. China’s thousands of years of history, language, geography, culture and ideologies, are constantly evolving without a fixed image. These myriad factors, though constantly changing and reshaping, can never be completely erased of its binding reality by history. Contemporary China is the result of a gradual layering process through history.

For example, one could say that China is rooted in Confucianism. This is not inaccurate. But there also exists Taoism, which was born and developed in China; Buddhism that influenced and entered China during the Han Dynasty; and other Western influences and thoughts that shaped China in the modern era (such as the spirit of enlightenment, humanism, and even the basis of justification for the legality of today’s government – Marxism.) These influences have all converged with the lives of the people in China. Whenever crises arise in Chinese history, one question seems to predominate: with such rich histories and cultures, do the Chinese really have a source of faith?

The countless images of China are as complicated as the maze that led a China professor to kill an overseas sinologist in Jorge Luis Borges’ short story, El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan (A Garden of Forking Paths). In it, Borges raises the eternal question of who can represent China. It is precisely this inability to find a simple representation and summary of China that makes discussion of contemporary Chinese literature even more meaningful. Throughout history, literature has always been a complicated form of art that holds value in the implicit and sublime. It is this implicitness and complexity that holds out in the fight against the voice of dogmatic ideologies and struggles against an oversimplification of the divide between the east and the west. As such, the most effective way to meander through the complexities and multiple images of China is probably through literature. Contemporary Chinese literature, like the multiple images of China, is a maze, not with the intent to confound, but as the only possible route to understanding the country.

Dan S. Wang, a second-generation Chinese-American artist, has also been drawn to the metaphor of the maze. In his works, the map of his ancestral hometown Shandong is transformed into a maze, the end of which may be a fairyland as told in Chinese myths or perhaps just the remains of a forced demolition. Through his maze, we see Wang’s identity search as a Chinese born and bred in America. At the same time, Wang’s artwork gives a hint of the disorienting effects of globalization and modernity – are we really left with no other escape routes?

The map is a maze, and the maze is also a map. The maze of contemporary Chinese literature provides its readers with a map to enter the realities of contemporary China, and perhaps a possible way out of the maze and into China’s future.

Xiaoyu Xia is a graduate student at Fudan University concentrating in contemporary Chinese literature and mid-20th century modern Chinese literature. Contact her at xiaoyu_lazur@163.com.

Sophia Ng is a 2013 graduate of Fudan University, where she majored in Chinese language and literature. She is currently training at Singapore’s National Institute of Education to become a Chinese language teacher. Contact her at sophia.ngcx@gmail.com.

This article appears in the November 2013 issue of China Hands.