QI HANG CHEN analyzes the Belt and Road Initiative five years after its announcement to gauge the early economic, environmental, and strategic returns.

Introduction

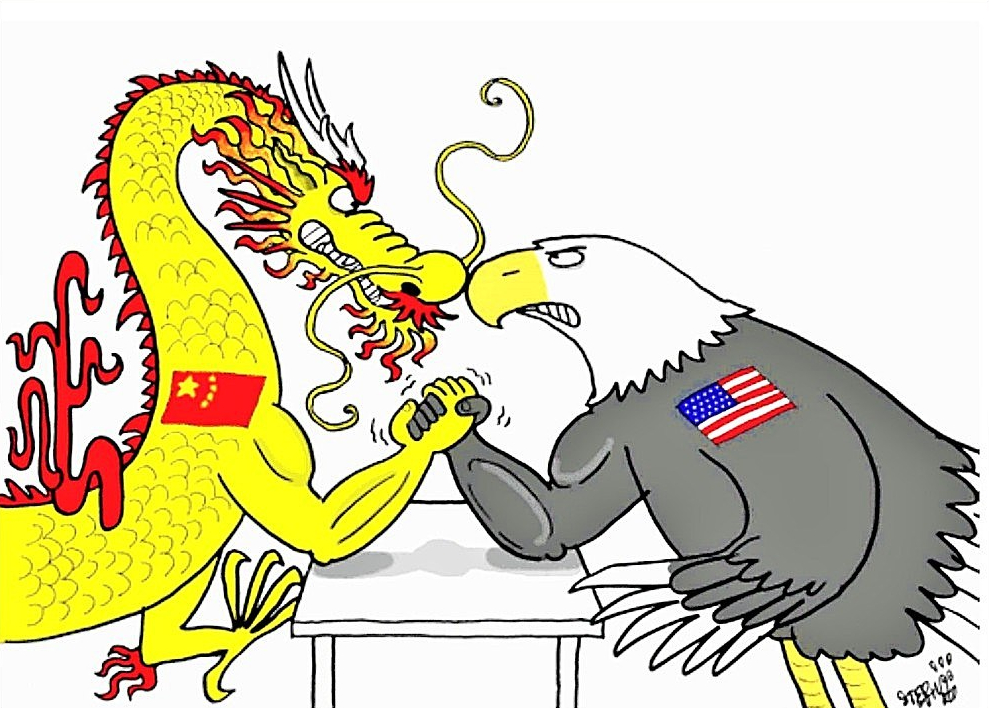

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as One Belt, One Road (OBOR), is China’s most ambitious infrastructure development project. It is also the largest overseas investment plan by any single country, dwarfing the Marshall Plan in comparison. It will have dramatic consequences for China, its BRI partners, its main geopolitical rival – the United States – and even the international political and economic system. The sheer monetary input – including environmental and socioeconomic outputs – has the potential to reshape the contemporary world order. However, it is also such a new initiative – and one of such colossal magnitude – that not enough time has elapsed to produce conclusive remarks about its implications and future. For this reason, the BRI is one of the most fascinating topics of our day. We know little about its long-term environmental impacts, risks and costs, nor about how a drastic influx of foreign direct investments would shape the economies and political systems of the smaller BRI countries. We know little about what the BRI means for China’s rise as a global power, and the stability and composition of the contemporary international order. Yet, the pace of its introduction, breadth of its acceptance by major powers, and sheer ambition of its blueprints require global attention, not least because discussion in these early phases may help shape outcomes for many years to come.

In this paper, I will adopt three existing analytical lenses – environmental science, environmental economics, and international relations to show three parts of the puzzle. Each aspect will present existing literature to analyze BRI and a rising China from a different angle. I will argue in this paper that a multidisciplinary approach may help us understand the comprehensive set of implications and significance of the BRI. I argue further, upon a comparison of these three approaches, that to understand the BRI beyond the framework of infrastructure and energy development projects, a multidisciplinary approach needs to be anchored by the analytical lenses of international relations more than any other discipline. In order to truly understand the drivers, implications and prognostications of the BRI framework, we need to contextualize it to how and why a rising China sees its expanding hegemony, and its relations vis-à-vis smaller emerging markets in surrounding regions.

I will start by giving a brief overview of the facts of the BRI. In the section on environmental science, I will present what current literature might say about the environmental impacts of the BRI. In the section on environmental economics, I will discuss the risks of Chinese-dominated investments along the BRI, and opportunities for green finance to make a systemic difference. In the section on international relations, I will discuss China’s long-term motivations, intentions and grand strategy, as well as its concerns in nontraditional security, so as to illuminate why China is embarking on the colossal mega-project. Lastly, in the discussion section, I will bring together all three sections and underline the benefits of taking a multidisciplinary approach to analyzing the BRI. I will also evaluate which lenses might be more useful in informing future discussions and open areas for future research.

As a caveat, this paper is meant to inform audiences interested in a preliminary analysis of the BRI early in its implementation. It, by no means, takes a deep dive into specific issues, such as the string of pearls theory, debt-trap diplomacy, environmental and climatic hazards. Because of the short time frame that has elapsed, this paper is limited by the scarcity in peer-reviewed literature on the BRI and draws heavily upon publications by think tanks, newspapers, and expert opinion pieces. This paper also only analyzes the BRI through three analytical lenses, missing out on others — for example, international political economy can shed much light on how the BRI has impacted regional and international trade and flow of natural resources, goods and services. Case studies of early BRI projects like Sri Lanka’s Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport and Hambantota Port, and Pakistan’s Diamer-Bhasha dam reveal early risks and pitfalls for BRI beneficiaries. However, in writing this paper, I hope to contribute to a pool of more broad, interdisciplinary analyses of the BRI that focus on both microcosmic implications and macro-cosmic overview of intentions, designs and strategies behind the BRI.

What is the Belt and Road Initiative?

The Belt and Road Initiative or “One Belt One Road” (BRI, or OBOR), proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2013, is a massive economic initiative that attempts to revive the old Silk Road on land (the “road”) and establish a new maritime route (the “belt”). The BRI is an ambitious investment project that goes beyond infrastructure, although roads, railroads, and ports are at the center of the program. It also includes “anti-poverty programs, emergency food aid, health recovery projects, and education opportunities for countries” (Friends of the Earth, 2016). It should be important to note that the BRI is the umbrella mega-project that encompasses smaller individual projects that were already ongoing before its formal announcement in 2013 – many of its earlier predecessors were then subsumed under the larger BRI. Some of these small projects were controversial even before the BRI, such as damming projects in the Mekong delta.

The mega-project itself comprises two parts. The first is a collection of overland projects – the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), that spans from Central Asia to Eastern Europe. There are six key components to this: (i) the China-Mongolia-Russia Corridor, (ii) the New Eurasian Land Bridge, (iii) the China-Central Asia-West Asia Corridor, (iv) the China-Pakistan Corridor, (v) the China-Bangladesh-India Corridor and (vi) the China-Indonesia Corridor.

The second is the Maritime Silk Road (MSR), which seeks to span across the South China Sea, the Andaman Sea, northern parts of the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea and reach the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal. Along the entire length, China aims to and has already constructed seaports in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Somalia, Greece as well as a special economic zone in Suez, Egypt.

China has spent $300 billion and plans to spend another $1 trillion within the next decade. In general, it is a comprehensive foreign investment package from China to smaller, emerging markets along the BRI. While China is overwhelmingly the largest investor (and lender) in the BRI, other partner countries participate as well, through direct bilateral investment agreements and multilateral development banks (MDBs) such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), albeit in negligible amounts.

China is building itself to be the largest export and import partner to as many countries as it can reach; currently this number sits at 92, already far more the second-highest – the US sits at 57. The remarkable speed at which China has risen is impressive. The BRI will reflect this continuing push for economic influence; the project will target emerging markets in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, Russia, the Baltic states and Eastern Europe.

In the economic sectors, the BRI will also target a few key industries: energy, infrastructure, transport, aviation, logistics, agriculture, and communications. Many of these sectors will have significant environmental impacts; this will be the focal point of this paper and will be discussed in later sections.

The BRI finds its origins in Xi’s stated desire “to promote the economic prosperity of the countries along the Belt and Road and regional economic cooperation, strengthen exchanges and mutual learning between different civilizations, and promote world peace and development.” (“Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road”, 2015) The BRI revolves around five key pillars, which China’s leadership and opinion-makers seem to respect diligently, at least in public forums and government-run media: (i) policy coordination, (ii) facilities connectivity, (iii) unimpeded trade, (iv) financial integration and (v) people-to-people bonds. The design reflects not only China’s commitment to economic growth, but also collective prosperity with BRI countries. It positions itself as antithetical to the wave of protectionism sweeping across the Global North and the hegemonic voices of the US and Western Europe in international economic and financial institutions. The BRI follows China’s other ambitious reforms of the international financial system – the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB), a counter to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and World Bank, as well as its panoply of homegrown international investment banks. China is also placing emphasis on cultural exchange as part of its plan to expand its soft power and regional and international influence.

An Ominous Sign for Climate and the Environment?

From an environmental science perspective, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) shows mixed risks and benefits, and there is no consensus among policymakers and analysts on whether one will outweigh the other. Time is the main factor in this ambiguity; because the BRI was only proposed in 2013 and since has seen its earliest stages gradually implemented in some parts of the world, much of what is planned – and what is not yet – is still to come. Literature on the BRI is thus sparse, and often not from peer-reviewed sources.

Additionally, not enough time has elapsed for studies to make meaningful, long-term conclusions, and the evolving nature of the project makes it even more difficult to extrapolate the future. However, several areas of the project that beg more extensive research have been identified: These include “detailed estimates of the project’s water and energy needed, including an evaluation of trans-boundary waters and how these should be managed; a full assessment of the project’s potential environmental and ecological impacts, together with options for remediation; and a complete appraisal of the geologic hazards that may arise as a result of the project activities.” (Li et al., 2015)

What is certain though, is that both risks and benefits exist. Potential areas for environmental protection and improvement include sustainable energy infrastructure – particularly in solar and wind, more efficient transportation infrastructure, transfer of sustainable development technologies and further development of green financing, as well as increased economic wealth that can facilitate transitions into green education, policies and economies (Tracy et al. 2017; WWF, 2018).

The purpose of this section is to focus instead on the environmental risks and costs that are already happening due to the BRI, as well as projected costs and risks given past environmental theories and case studies.

It should also be noted here that the within the environmental science discipline, there has been a tradition of measuring environmental degradation using carbon dioxide emissions as a proxy that has become a predominant paradigm (Hafeez et al., 2017). Discourse on environmental impacts of the BRI, in contrast, focuses on a much more diverse set of environmental indicators and systems, as seen in the analyses further in this section. For example, disruption of natural habitats and local ecosystems, loss of biodiversity, over-extraction of water resources, land erosion, are also negative perturbations to planetary systems that are important foci and given the appropriate concern and attention when it comes to studying the BRI. Much attention in recent years, for example, has been given to endangered species threatened by the BRI, such as the Amur tiger and the Far Eastern leopards, whose natural habitats are being increasingly fragmented by the construction of railway corridors between China’s Rust Belt in the Northeast and Siberia (Tracy et al., 2017).

A 2018 paper jointly published by the World Wildlife Fund and HSBC provides a useful framework for considering seven different elements of BRI’s environmental impacts, clearly demonstrating the diversity of environmental indicators environmental scientists pay attention to when it comes to studying the BRI. Environmental risks and costs of the BRI are measured by the project’s (a) inputs, which include (1) ecosystem use, (2) water use, (3) use of other resources, and (b) outputs, which include (4) greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, (5) non-GHG emissions, (6) water pollutants, and (7) solid waste (WWF, 2018). An eighth element that should be under consideration as well is the (8) increase in overall population in BRI corridors because of the project, that will compound the seven factors (Li et al., 2015).

The most contentious and damaging aspect of the BRI is the export of coal-fired power plants to countries in the BRI. In fact, infrastructure and development projects along the BRI will be predominantly powered by coal-fired plants, despite China’s commitment to U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Climate Accord, and a vision of a “green, healthy, intelligent and peaceful Silk Road” (WWF, 2018, pg. 11). It must be noted that these agreements and guidelines are still in infancy, are largely non-binding, and therefore present no viable punishment for a China that wishes to deviate from such a vision.

China is already the world’s largest exporter of coal-fired plants, and the BRI will only entrench this status (WWF, 2018). The immediate impacts are clear: the “shadow ecology” (Dauvergne, 1998) of the BRI means that while China pivots sharply towards sustainable development and green policies domestically, the overall perturbation to planetary systems will not decrease, and in fact, might even increase. China is merely shifting its carbon footprint to other smaller and weaker countries along the BRI, and China’s domestic efforts at going green have not fully translated into or impacted its investments and development abroad (Hafeez et al., 2017; Tracy et al., 2017). China’s commercial banks, in particular, face little to no restriction on their funding of coal-fired plants, which continues to contribute significantly to China’s overall carbon foot-print, if its overseas investments were to be considered as well (Gallagher & Qi, 2018).

Supplemental forms of energy to coal, natural gas and oil, are also potentially problematic for the environment. One of China’s principal goals for the BRI is to ensure energy security, and its partnership with the Central Asian countries rich in oil and gas resources will mean that it can transport its energy more safely without being vulnerable to controversies in the South China Sea and US interference in the sea lines of communication (SLOCs). The building of pipelines in Central Asia has already had effects on local environment; the North Caspian Operating Company, for example, has to replace its pipelines in 2014 due to leaks (WWF, 2018). China’s BRI has not represented any substantive decoupling from non-renewable energy resources; import of Russian crude oil has doubled from 2012 to 2017 (Tracy et al., 2017).

Furthermore, roads and railroads through formerly inaccessible territories bring habitat fragmentation and exploitation of local resources, with concomitant environmental damage and biodiversity threats (WWF, 2018). Moreover, deep-water ports, a crown jewel of the BRI, have impacts on coastal ecosystems, small-fisherman livelihoods, and coral reef systems. They also bring pollution from shipping fuels into coastal waters (WWF, 2018).

While the opening of coal-fired plants abroad and the continued dependency on oil and gas are already a target of controversy, other forms of energy will also have significant environmental impacts. Even renewable energy resources, such as hydroelectric, solar and wind power, have consequences as well. Hydroelectric energy generation through dam-building will disrupt ecosystems (including the movement of migratory fishes, sedimentary distribution, river and lake nutrients, the risk of hypoxia etc.), and natural habitats, divert rivers, change flows and distribution of water resources, and force relocation. The BRI is already seeing impacts in the Mekong delta, where dam investments are putting potentially 64 species in danger (WWF, 2018).

The manufacturing process for solar panels is also known for its highly toxic discharge. The perturbations to biotic systems along the BRI from an environmental science perspective seem inevitable. At stake is whether they can be minimized, and if net environmental gains can be made in the long run. Some critics argue that solar and wind power, with their low environmental costs, have been sidelined within the BRI with limited commitment (WWF, 2018). To the extent that this is true, it reflects the disconnect between green domestic policies in China and a lack of commitment to hard environmental regulations abroad; China is the world’s largest manufacturer of wind turbines and solar panels (Tracy et al., 2017), but this has not translated into commitment to solar and wind power in the BRI. In the short run, there is unlikely to be a dramatic pivot from coal power to more low-impact renewables, though the public and local push-back against coal-fired plants have been vocal and strong. The Chinese government, known to be susceptible to changing public opinions, has shown some signs of willingness to shift towards minimizing carbon output along the BRI, though only more time will reveal the actual level of commitment to legislative, financial and environmental reform to the BRI.

The increase in economic activities along the BRI will also result in faster depletion of available water resources, and the increase in population engendered by the prospective economic boom will further exacerbate the situation. This is in particular a very real threat in the first stage of the BRI – the Central Asian corridor. Kazakhstan and Mongolia, China’s immediate neighbors, and two important allies in the BRI, are located in an arid geographic region which cannot sustainably support massive increases in water use (Li et al., 2015), be it for manufacturing and production, energy generation, or human consumption (WWF, 2018). Many of these activities may also pollute existing water resources beyond the point of sanitary and safe human consumption and support for local ecosystems, therefore further exacerbating water shortage (WWF, 2018). This will be particularly problematic from a population perspective – the three billion people living along the BRI will see increased numbers along with economic boom, and that may further strain both land and water resources, particularly along strips in Central Asia where these resources are scarce to begin with (Li et al., 2015). Depletion of water resources can also have larger impacts, such as the change in regional climate, diminution of natural habitats, and the disruption of local ecosystems and biodiversity.

Apart from environmental impacts specific to localities, the BRI has systemic environmental impacts as well. With increased economic activities comes increased carbon footprint. Studies have shown that there is a direct correlation between economic growth and carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere (Hafeez et al., 2017). One mechanism in which this relationship manifests in is the transportation of goods and services – in shipping and land transport. Apart from localized environmental impacts of increasing international shipping in oceans, rivers and lakes, as well as the construction of road and rail infrastructure, such as the proliferation of exogenous species, hypoxia from fuel waste, disconnecting rivers from floodplains, posing barriers to travelling mammals, and dissecting natural habitats into habitat islands, increased transport also contributes to global emissions of greenhouse gases (Tracy et al., 2017; WWF, 2018). Cement production, a key step in the massive infrastructure development scheme that is the BRI, produces large quantities of toxic waste, greenhouse gases, toxic gases, and also requires large amounts of water resources and energy (Tracy et al., 2017), presumably generated by coal-fired plants. Another mechanism is that with economic growth, consumption of goods and services increases, which leaves more carbon footprint (Hafeez et al., 2017).

Some, however, have argued that based on the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC), the initial degradation of the environment due to economic growth will be mitigated by future economic growth, and development in scientific and technological innovations (Hafeez et al., 2017). Within the environmental scientific community, there is no consensus on whether the EKC will hold true for the BRI (Hafeez et al., 2017; Tracy et al., 2017), or in general at all, for that matter. As previously discussed, economic growth has a positive correlation with environmental degradation, and whether or not the innovations that come along with growth can mitigate the increase in consumption, production and pollution, is unknown. For this reason, there is much anxiety, ambivalence and ambiguity about the current impacts and future environmental consequences of the BRI.

A Debt-Ridden Framework

Literature pertaining to the economic and environmental impacts of the BRI focuses mainly on one thing: finance. There is near-universal consensus in the contemporary literature on the BRI that how the massive energy development and infrastructure projects of the BRI are financed will have momentous consequences, as well as for global efforts for combating climate change. Intentions are important to examine because of China’s overwhelming economic dominance along the BRI; its financial control over the mega-project has significant implications for the future of legislative, environmental and economic environments of BRI countries.

Financing the BRI is a colossal task. There are several key financial stakeholders in the equation. First, there are the two main groups of financiers – the first is a collection of Chinese policy and commercial banks, owned by the Chinese government. They include the likes of China Development Bank, China Import-Export Bank, Industrial Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), China Construction Bank (CCB), Bank of China (BOC), Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) and the Bank of Communications (BOCOM). Not only are they providing loans to finance the various projects along the BRI, but they are also expanding their physical presence in BRI countries (Friends of the Earth, 2016). The second group are state-owned enterprises (SOEs), including energy, oil, gas, telecommunications and shipping giants in China owned by the Chinese government (Friends of the Earth, 2016).

There exist other important financial actors. The Silk Road Fund, for one, is a private equity fund starting at $40 billion, jointly established by a couple of Chinese banks and the Chinese foreign reserve. There are also several other multilateral development banks (MDBs) that involve a multitude of regional state actors, the most prominent of which are the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), headquartered in Beijing, which is funding projects in South, Central and Southeast Asia, as well as the New Development Bank (NDB), which has authorized $100 billion towards the BRI (Friends of the Earth, 2016).

The project, as previously discussed, has already received large sums of investments from the Chinese government through the main financial actors – Chinese banks and state enterprises, as well as other sources, such as the AIIB and the NDB. This number in reality, differs quite widely. The Paulson Institute (2017) estimates that some $200 billion has already been committed by Chinese policy banks in the project, with $40 billion reserved for the “Silk Road Fund”, a joint venture between the Chinese government and the Chinese Foreign Reserve, to which Xi pledged an additional $14.5 billion (World Resources Institute, 2017). Xi also pledged approximately $100 billion from various Chinese financial institutions on top of existing pledges (World Resources Institute, 2017). A Greenovation Hub estimate (2016) states that the capital demand for some 60 BRI projects might reach $2.5 trillion in capital demand. The Paulson report (2017), based on PwC estimates, claims that some $5 trillion will be required for total infrastructure investment over the next 30-40 years. It also reports $890 billion in investment deals already announced.

China is overwhelmingly the largest investor and lender in the BRI mega-project. Other BRI partner countries contribute, through bilateral investment commitments and/or multilateral development banks (MDBs) like the AIIB and ADB, but the amounts they pledge to the BRI are negligible compared to China’s involvement. By a Silk Road Briefing estimate (2017), MDBs – dominated by Chinese stakeholders to begin with – contribute only 4.94% of the funding, while bilateral agreements only 0.17%. The four biggest Chinese commercial banks alone fund some 83% (Silk Road Briefing, 2017).

Estimates of how much investment and capital are needed for the completion of the entire project vary quite greatly. Some are much more ambitious compared to the Paulson Institute. According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), as the World Resources Institute reports (2017), more than $26 trillion will be needed infrastructure investment through 2030 alone, and at least $8 trillion to tide over 2010-2020 (Greenovation Hub, 2016), since there is a severe shortage of infrastructure development in much of the developing countries along the BRI corridor. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimate through 2030, according to Green Finance Initiative (2017) is through the roof, at $89 trillion.

Investments and capital flow will be quintessential to the BRI projects. Currently, there is a mixed view on how sustainable BRI is from a financial perspective. There have certainly been concerns and even accusations that the BRI was designed to cater to Chinese economic interests, expanding China’s reach into markets in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, Eastern Europe and Africa (China Dialogue, 2017), and serves as essentially the external strategy for reforming and modernizing the Chinese economy after the 2008 financial crisis, as well as finding new hosts for China’s excess production capacity and foreign-exchange reserves (Brookings Institute, 2017).

There are signs that support this line of argument. For one, funding is predominantly from public financial institutions, and overwhelmingly from China. There is a lack of public-private balance (Green Finance Initiative, 2017), and far less contributions from smaller countries along the BRI, despite their positive outlooks about the project itself (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2017). The lack of active involvement in terms of investment from host countries is worrying in the sense that it allows China’s state-owned financial institutions to fund the BRI in its image – which is the lack of concrete financial governance in support of sustainable development, environmental protection, and commitment to fighting climate change. These BRI countries also have little incentive to turn away China’s lucrative investments – they are in desperate demand for infrastructure and economic development (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2017). China is also less than engaging with private companies, civil society organizations and local communities in countries along the BRI, unintentionally or by design (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2017).

By putting up minimal resistance to Chinese capital and having little private sector engagement to counter Chinese state interests, other BRI countries are allowing China to influence their energy and infrastructure policies (Forbes, 2017) – and, as noted earlier, the direction that China is taking is not reflecting the same kind of pivot towards green and sustainable growth that we are seeing in China’s domestic economy, and not reflective of substantive, sincere and fundamental efforts at clarifying how China and countries along the BRI will address environmental issues (Friends of the Earth, 2016). At the minimum this is true right now – for example, as discussed from the previous section, China has not moved away from investing in coal-fired plants and hydroelectric power in the BRI, both of which have drastic environmental consequences.

What compounds this is that the lack of an “embedded, binding decision-making mechanism” in the BRI (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2017) – something that was by design meant to attract BRI partners and bolster China’s hegemonic position in its attempt to create a rivalrous economic and political system to the liberal world order led by the U.S (Ikenberry, 2008; Ikenberry, 2011). This is a double-edged sword – the flexibility and voluntary nature of participation means that there is also minimal binding effect of capital flow and investments in mandating green and sustainable energy and infrastructure development in BRI countries. Additionally, these states are early in their economic development, crave infrastructure and investment, and have weak environmental governance and legal structures. The BRI has the potential to be an environmental disaster, given the lack of mandatory commitment and poor environmental governance in addition to the dearth of private sector and NGO stakeholders in investment processes, weak host country input, and the Chinese reluctance to check and balance its own investment plans against environmental and sustainability standards and replicate its own domestic green economic policies abroad.

However, most of the literature looking at environmental economics in the BRI agrees on the abundance of opportunities in making strong progress towards systemic sustainability and environmental protection. Two key fields with high demand for investment – and key centrality to the BRI altogether – are energy and infrastructure, and they have dramatic impact on both the environment and the climactic and planetary systems. Because of this, “green finance” has captured the attention of those who are studying the environmental economics of the BRI and those who are seeking positive changes in the two fields. In trying to leverage the trim tab that is financing, many hope to use a small positive perturbation to engender systemic transformations.

Some call for greater involvement of MDBs in the BRI, and stronger commitment by these multilateral financial institutions to existing green policies and principles; simultaneously, private sector entities should have a much greater presence, through a process called “crowding in”, which is to introduce private capital to balance out the interests of other financial players, including MDBs and Chinese state-owned banks (Green Finance Initiative, 2017).

On another note, some argue that there should also be a harmonization and standardization of existing green finance policies and principles. Currently, some standards, such as the Chinese Catalogue standards used to measure clean coal projects in Pakistan, are more lax than international standards set by the CBI or ICMA (Green Finance Initiative, 2017). Additionally, there are many Chinese stakeholders, such as the China City Development Foundation, that are working on developing their own accreditation and standards (Green Finance Initiative, 2017). There have been some attempts at standardization, such as that by the Green Finance Committee of China Society for Finance and Banking, in conjunction with the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), Investment Association of China (IAC) and China Banking Association (CBA). A 2017 policy paper they published call for greater adherence to environmental laws, regulations, green supply chain principles, U.N. Principles for Responsible Investment in overseas investments, as well as understanding and mitigation of environmental risks, particularly in the BRI. Others call for greater dialogue about and commitment to U.N. Sustainable Development Goals and other international environmental and climate agreements such as the Paris Accords in institutions such as the G20, while strengthening China’s domestic regulations on how Chinese investments are made abroad by Chinese financial institutions, to shift gears towards green finance in the BRI (Greenovation Hub, 2016).

In fact, green finance might very well be in China’s favor – and thus gives China economic incentive to commit to funding the BRI with conditions for sustainable development policies attached. The idea of “co-benefits” – using economic incentives which are otherwise secondary objectives to say, environmental scientists more concerned about protection, conservation and sustainability, as the main incentive to induce green policy behavior – is very much relevant to the BRI conversation. The principle of co-benefits is that policymakers should strategically target and encourage certain activities to reap both tangible (economic) and intangible or abstract (environmental and climate) benefits, because the intangible benefits on their own are difficult as tools of persuasion to get the public on-board (Younger et al., 2008). There are arguments being made about green finance actually incurring lower costs for China over the long run (Green Finance Initiative, 2017). In energy development, for example, many forms of renewables such as wind and solar, are already matching or even beating cost per unit as compared to non-renewables (WWF, 2018). China, in particular, is already endowed with the largest solar panel production capacity in the world. Financing sustainable infrastructure and energy development in other BRI countries will be easier for China because of its unique ability to be price-competitive in these sectors. Furthermore, the expansion of BRI to these smaller, but largely untapped infrastructure and energy markets presents an abundance of opportunities to export China’s sustainable development technologies, goods, services and excess capacities. On the other hand, these BRI countries have little reason to reject China’s green-financed investment projects – opening doors to transforming their energy and infrastructure sectors, building up stronger environmental governance standards and legal institutions (Tracy et al., 2017).

In general, there is consensus that there is much room for improvement in the BRI for green financial regulations, coupled with sustainable energy and infrastructure policies in BRI countries. On the flip side, the BRI program reflects an abundance of opportunities to not only see localized shifts towards sustainable development, but a systemic change in economic paradigm led by China.

A Rising China in a Changing Global Order

The study of international relations is fast evolving. In fact, in today’s globalized world, nontraditional security domains – such as water security, energy security, food security and climate security – are increasingly overshadowing traditional, military security issues. These trans-boundary issues, often blind to nation-state identities and sovereign boundaries, are some of the trickiest, most controversial, and most difficult to solve – often requiring collective efforts and shared but differentiated responsibilities to overcome. These issues, simultaneously, often change the regional balance of power, and drive great power dynamics and strategic interests.

The examination of the BRI and its impacts through the lens of international relations is fundamentally an understanding of China’s increasingly prominent role in nontraditional security domains, and China’s intensifying concern about and commitment to seeing such domains as quintessential to its own national security, perhaps even more than traditional military security. (It should also be noted that in most discussions and analyses, economic security has also been lumped together with the more distinctively nontraditional security domains, because of the intrinsic connectedness of economics to food, water, energy, the environment, and climate).

The BRI is the central cornerstone to contemporary Chinese grand strategy and the key to understanding molding Chinese foreign policy. Many see it as not just the externalized portion of China’s strategic economic reform (Johnson, 2016), but also China’s expansion of its soft (and some would even argue, hard) power to far-flung pockets of the world. While some argue that this is the Chinese attempt to challenge and reconstruct the existing hegemonic structure – one that is a US-led liberal international order – in its own image, others argue that China is merely trying to mimic the US and replace merely the existing hegemon without destabilizing the entire system. It would not be inappropriate, as some have done, to call the BRI the Marshall Plan equivalent of the 21st Century – after all it is much bigger in scale; while others, in particular the Chinese, contend with the imposing nature of such a comparison, and point to the voluntary nature, pluralistic elements and multilateral engagement of the BRI as a response to the institutional hegemony of the Global North.

It should also be noted that within the broad spectrum of international relations theories, the BRI in its institution-building capacities and the expansion of Chinese soft power seem to draw more upon liberal and constructivist paradigms. Nevertheless, realist perspectives cannot be disregarded, such fundamentally the national concerns of the BRI is whether or not such a framework seeks to increase China’s national economic capabilities in a way that can reshape the global order to serve as some sort of counterbalance to the Washington consensus – the “string of pearls theory,” as discussed later, also heralds the potential expansion of Chinese naval presence into the Indian Ocean. This paper, however, does not seek to account for which international relations paradigm has the greatest explanatory power. Rather, it offers a more holistic and amalgamated view of the BRI through the international relations lens as a whole to deduce the drivers, implications and prognostications of the BRI.

Regardless of these debates of Chinese grand strategy and foreign policy intentions and actions, looking at the BRI through an international relations lens will illuminate these questions: Why does China care about nontraditional security domains, such as food, water, energy, environment and climate? What is China’s long-term plan for its national security, and its rise to become a regional hegemon in a multi-polar world?

Current literature offers a response to the first question that is almost unitary. Some argue that China is operating on the foresight that the next big war will be fought over natural resources, particularly given their scarcity (e.g. energy resources and fuel), inequitable distribution (e.g. water and food) and systemic repercussions (e.g. environmental degradation and climate change). Nontraditional security is becoming increasingly important, perhaps more so than military conflict in many aspects (Gill, 2010). International institutions and legal frameworks over these domains are much less developed and robust as compared to the traditional military realm, which presents both current vulnerabilities and future possibilities for China to take leadership and shape the system. For these reasons, China has a large stake in the game.

What makes China’s commitment to nontraditional security domains even more necessary and exigent is China’s natural disposition. It is an extremely populous country with a large demand for electricity, energy and power; its arable land area relative to its people’s food consumption is small, especially compared to countries like India; its population is both responsible for and bearing the brunt of pollution, environmental degradation and climate change (Len, 2015). China has a real incentive to focus on nontraditional security because of its intrinsic vulnerabilities.

The BRI is a key cornerstone in alleviating these vulnerabilities. For example, the maritime component of the BRI, which focus on building deep-water ports in places like Gwadar, Pakistan, and forging stronger partnerships with ASEAN giant Indonesia, help secure the sea lines of communication (SLOCs), safeguarding the safety and prosperity of Chinese trade, and energy imports (Johnson, 2016; Len, 2015). The latter is especially important given that China has become a net importer of fossil fuels since 2009 (Len, 2015). The overland component of the BRI, a large part of which falls in Central Asia, a region rich in oil and gas, is also meant to create an alternative route for China to ensure its energy security for its growing economy and large population and industries, while diversifying away from the traditional sea routes through Southeast Asia and South Asia, which are filled with US allies interested in containing China’s rise (Du, 2016; Johnson, 2016; Len, 2015; The Atlantic, 2017).

The BRI is also useful in mitigating some of the undesirable effects of committing to nontraditional security. In China’s fight against pollution and environmental degradation within its sovereign borders in the past decade or so, in addition to the natural effects of the economic slowdown China has experienced in the past years, China also found itself having an excess of industrial capacities, particularly in coal-fired production, and associated expertise and manpower (Du, 2016; The Atlantic, 2017). This is also another reason why China is so invested in the BRI – its commitment to nontraditional security domestically has produced a surplus that needs to be exported in the “going out” strategy that is the BRI.

There are of course also economic (and non-environmental) dimensions to China’s embarking on the BRI. One, as I have discussed above, is the need for economic reform and revitalization after the financial crisis of 2008 – the slowdown means that China has to find new ways to export its excess and find new markets for public financial institutions and SOEs to invest in and develop (Du, 2016; Johnson, 2016). The other aspect is that China is trying to replace the US dollar with its own renminbi as the hegemonic currency in global financial flow (Du, 2016). Additionally, China is using the BRI to rid itself of US government bonds and opt to directly invest, making better use of its $4 trillion foreign reserves (Du, 2016; The Atlantic, 2017). The BRI of course, naturally reinforces Chinese trading presence in neighboring regions as well as internationally, and safeguard both the security of Chinese goods as well as overall Chinese economic interests. Finally, the BRI will also help to develop China’s peripheral provinces in the Northwest, such as Xinjiang, where poverty still reigns, of which social instability may be a product. Economic security, as seen in the examples above, is also of key interest to the Chinese government – many also consider it as part of the nontraditional security domains.

Current literature, though limited, also offers insight into the second, and perhaps the bigger underlying question – what is China’s grand strategy, and how is the BRI helping it achieve that? There are contentious debates around China’s long-term intentions and visions. Some argue that China is a rising power, and thus by realist logic, would seek to challenge American hegemony and overthrow the current international system, resulting inevitably in military, or at the very least, severe economic conflict. Others, such as John Ikenberry, disagree by arguing that China will try to replace the US as the leading hegemon within the current system, but not seek to dispose of the system altogether, and instead benefit disproportionately from it as the US has done. While this paper will not focus on this debate, I will however lean towards Ikenberry’s assumptions and arguments, simply because China’s actions largely stick to a status quo (in the South China Sea, for example, albeit one that it set for itself), and because China has been increasing its involvement in international institutions, economic interdependence, and multilateral partnerships while tackling trans-boundary issues such as international peacekeeping and climate change.

If China can be understood as trying to usurp the US as the systemic hegemon, the BRI is China’s golden ticket to earn that position. The key to doing this is the expansion of its soft power. Such an expansion manifests itself in several ways, obvious and subtle, in the BRI.

First, China is practicing soft (or perhaps hard) economic imperialism with BRI countries. By offering astronomical amounts of foreign direct investments (FDI) in countries which are capital-poor and often desperate for capital inflow and investments, China positions the BRI to be irresistible to these emerging and developing economies. Because these countries end up being so economically tied to, and more importantly, dependent on China, China gains new political allies and consolidate existing relationships (Manuel, 2017). Indonesia is a prime example of this – by offering them investment sums that they cannot possibly turn down, China gains a new solid ally in ASEAN, and was able to push its own geopolitical agendas forward when ASEAN failed to reach a consensus on statement in response to China’s activities in the South China Sea.

On a related note, by aggressively investing in vulnerable emerging markets, China is able to dictate the rules, regulations, norms and systems in these countries, which often lack proper financial, economic, legal and environmental framework and structures. That allows China to essentially step in and shape BRI countries in whichever image it prefers, much like what the US did with the Marshall Plan in Western Europe.

Additionally, by loaning large sums to develop infrastructure in BRI countries, China finds itself in a win-win situation. If these investment loans were to be returned by these countries, then risks on these investments are mitigated. If countries are unable to return these loans, as Pakistan has for its BRI infrastructure projects, then China gains ownership of these key infrastructure projects, which are often environmental choke-holds of high geopolitical value to China. For example, the deep-water port in Gwadar is essentially in Chinese ownership, with China making 91% of all port income, because Pakistan is unable to pay back the investment loan (The Atlantic, 2017; Times of Islamabad, 2017); Sri Lanka recently handed over a key strategic port Hambantota to China because it defaulted on its investment loan (CNN, 2017; Schultz, 2017). Either way, China gains greater access to secure trading routes, key geopolitical points, and influence in BRI countries.

More systemically, the BRI represents China’s grand strategy of reshaping the international system in its own image. Not necessarily deconstructing and destabilizing existing systems, China recognizes the benefits of being the hegemon, and seeks to replace the US China backs up its rhetoric of a green, peaceful BRI with multilateral development financial institutions, such as the AIIB and ADB, that seek to promote more shared interests, equitable and pluralistic development, greater multilateral engagement, on a more voluntary basis (Du, 2016; The Diplomat, 2017). In fact, China emphasizes that the BRI is not the rebirth of the Marshall Plan – a unilateral effort by the US that can be interpreted as imposing and imperialistic (The Diplomat, 2017). The BRI is, according to China, a direct contrast to international institutions like the WTO and the World Bank, traditionally dominated by the hegemonic voices of the Global North. The intention of this design is particularly evident in Xi’s own rhetoric about the BRI. At the 2017 Belt and Road Forum, he emphasized the key tenets of the BRI: shared prosperity, harmony, mutual exchange of culture and economic goods, multi-polarity and greater equality of voices (Xinhua, 2017).

This is perhaps part of the reason why China has committed, in a dramatic pivot, to climate change issues as well as environmental protection and sustainable development. Apart from addressing its domestic challenges, and as much as China might shy away from the brunt and responsibilities of international leadership, China has styled itself as the forerunner of green policies and politics. Part of this is the desire for positive attention, legitimacy and international recognition especially by developing and emerging economies that suffer disproportionately from environmental and climate challenges and have the most difficulty in dealing with them and in going green. The other part is the hope of opening new markets for its own sustainability-focused sunrise sectors. Both logics demonstrate the reasoning behind China’s desire for green leadership. The BRI is quintessential to fulfilling this goal, and to continue to expand Chinese soft power. In this sense, China has great incentives to spread the idea and practice of sustainable development through the BRI to countries that have limited experience, expertise or infrastructure.

The BRI is wrapping itself in green rhetoric, but the behavior is starting to catch up, with more stringent regulations and guidelines (China Daily, 2017; South China Morning Post, 2018; The Atlantic, 2017), as I have previously discussed. If the vision of a green, peaceful BRI can be materialized, it would cement China as not just a military hegemon, but a great power with economic influence and prowess, and normative soft power and legitimacy to lead on trans-boundary issues in the nontraditional security domains (South China Morning Post, 2018). If the BRI were to be fraught with environmental hazards and degradation, local resistance, and the appearance of one-sided Chinese imperialism seeking only to benefit the Chinese, then the BRI becomes a self-defeating project which not only does not expand Chinese soft power but weakens mutual trust (Du, 2016), as well as its international credibility, reputation and standing (Reeves, 2013). There are already prominent case studies of resistance from BRI countries on these grounds, such as the Philippines, Myanmar, Mongolia, Cambodia and Laos (Len, 2015; Reeves, 2013). On this factor alone, China has a great imperative to improve environmental standards along the BRI, and thus engage in more positive international politics (Len, 2015) – its soft power expansion plan, and thus the crux of its grand strategy to rise to become the regional hegemon in a multi-polar world, is at stake.

A Comparison of the Three Analytical Approaches

The BRI is an environmental, infrastructure, energy development, financial and economic, political, institution-building as well as system-reshaping mega-project that spans across multiple disciplines. The three preceding sections discussed three of such disciplines, examining the BRI through the lenses of environmental science, environmental economics and international relations.

Albeit with some areas of overlap, each discipline presents a disparate picture of the project. To understand the triadic relationship of these three disciplines in explaining the implications of the BRI, Arnold Pacey’s 1983 work – Technology: Practice and Culture– provides a useful framework for thinking about this:

“So is technology culturally neutral? If we look at the construction of basic machine and its working principles, the answer seems to be yes. But if we look at the web of human activities surrounding the machine, which include its practical uses, its role as a status symbol, the supply of fuel and spare parts, the organized tourist trails, and the skills of its owners, the answer is clearly no. Looked at in this second way, technology is seen as a part of life, not something that can be kept in a separate compartment. If it is to be of any use, the snowmobile must fit into a pattern of activity which belongs to a particular lifestyle and set of values.” (Pacey, 1983, pg. 3)

Pacey’s concept of “technology-practice” deconstructs a piece of technology into its three aspects – technical, organizational and cultural. The technical aspect, something that most people would identify technology with, has to do with the superficial implications of technology – its mechanics, techniques, knowledge and essential activities. At the deeper level, are two other aspects of technology (Pacey, 1983, pg. 5). The organizational aspect is the understanding of technology’s political and economic implications, administration, public policy and producer-consumer relations (Pacey, 1983, pg. 5). The cultural aspect, on the other hand, is the understanding of the values, ideas and ideologies behind the technology (Pacey, 1983, pg. 5).

If the BRI can be thought of as one giant piece of technology – and in many ways it is an amalgamate of technologies across a large geographic span – then each of the three lenses adopted in this paper fits nicely into each of the three aspects of Pacey’s “technology-practice”.

Environmental science provides understanding of the BRI’s technical aspect and is important to analyzing the implications of the BRI exactly because of the “superficial” nature of its focus – on the environmental impacts (and opportunities) of the project. While on its own such analysis presents only a two-dimensional environmental cost-risk analysis of the BRI, the information and research generated by such a lens will form the basis for other conversations in environmental economics – for example, why green finance might be a highly exigent and necessary consideration – and international relations – for example, why China, a rising power interested in expanding its soft power and global influence against US hegemony might not want the poor media optics and actual repercussions of BRI’s environmentally degrading elements to hinder its grand strategy.

Environmental economics provides understanding of the BRI’s organizational aspect and is important to informing conversations on how China (and its partners) are funding the entire project, the types of financial stakeholders involved – SOEs, MDBs, Chinese banks etc., the relationship between the investor and the investees along the BRI, as well as key areas where Chinese economic dominance borders on imperialism and thus might create flagrant lack of sustainability, but also opportunities where Chinese economic strength can reshape and reform emerging economies through green finance to align with green growth and sustainable development. This lens of analysis proves to be quintessential to breaking down the BRI’s modus operandi, from which we can gain better understanding of what is being done and what can be done in the future to achieve specific goals, for example in green development.

Lastly, international relations theory builds upon the technical understanding of the BRI’s environmental impacts. It also addresses the lacuna in literature that environmental economics does insufficiently – the former answers the “why” question behind China’s embarking on the BRI, while the latter addresses mostly the “how.” The international relations lens provides deeper understanding of the cultural aspect of the BRI, and illuminates China’s long-term motivations and grand strategy, its concern with and mitigation efforts in nontraditional security domains, particularly in energy security, as well as China’s risk-aversion with regards to reputation loss from environmental hazards along the BRI in its institution-building, alliance-building, influence-buying, soft power-expanding path to greater hegemony and leadership within the international political and economic system. This lens provides critical analysis of the overarching design and intentions behind the BRI and more importantly, insight into China’s grand strategy, the BRI’s key role in enshrining and materializing it, and China’s principal ideologies and values of seeing itself as the “center of gravity” (The Diplomat, 2017) in East Asia and within the global system, where the overland Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road all lead back to China.

This paper shows the importance of understanding the BRI holistically. There is no singular lens that can account for the design and implementation of the BRI in its entirety. All three lenses, instead of contradicting and competing with each other, build nicely upon one another to give a fuller picture of China’s mega-project.

In the concluding thoughts to this section, however, I would make the case that the latter two lenses – environmental economics and international relations – make more compelling cases for people to be interested in and thinking of the BRI. While by means this is a discount of the environmental science analyses of the BRI’s environmental impacts, risks, costs and opportunities – and I have previously emphasized on the necessity of such analyses in informing higher conversations – environmental science analyses on their own will not inspire international action, and more importantly, China’s action for change. Environmental concerns on their own, decoupled from economics, financial flows, and international relations, will do little in persuading China to behave in a certain way. Howard French, in his book Everything Under the Heavens, cements Chinese determination, by arguing that “there was scarcely anyone who believed that the American protests or overflights or whatever other gestures might be mustered could alter China’s course” (2018, pg. 264). The same logic applies here – but if the right trim tab (Forbes, 2014) – a small entry point that can engender larger change within a complex system – could be found to tap into China’s interests and motivations, then change could be made.

Such opportunities, as discussed previously, present themselves in the domains of economics and international politics. Green finance, for example, could achieve both the effects of systemic spread of sustainable development ideals and practices, especially along the BRI where most of these emerging economies have poor green infrastructure, as well as lower long-term risk and better cost-return ratio for Chinese investments. On the other hand, commitment to more stringent green and sustainable development goals, regulations and frameworks along the BRI by China and its multilateral partners would go a long way in ensuring China’s own nontraditional security, as well as boost its international reputation, recognition and legitimacy as a global power and leader with growing influence and soft power, committed to trans-boundary issues and collective prosperity. For these reasons, I find that the lenses of environmental economics and international relations to have greater explanatory power beyond the mere implications of the BRI, but also offering better insight into what is to come – what is the likeliest future outcome for the BRI and China’s grand strategy – and what can be done – if opportunities where China can be socialized and incentivized into being a more accommodating player exist, and how, or otherwise. These two lenses present better opportunities for future conversations and expansion of current ones.

I will go further to argue that understanding the international relations dynamics behind the BRI is even more important than understanding economics. As previously discussed, economics only answers part of the puzzle – the “how” – rather than the “why”. Any multidisciplinary approach to the BRI must be fundamentally anchored in international relations. The BRI, as its core, is a Chinese quest for friendships – perhaps not as normatively strong as those between mutually understanding democracies across the Atlantic – but friendships of a new “Asian way”. China seeks to craft new, lasting alliances that go beyond a shallow understanding of mutual economic benefits, but a network of political and economic partnerships with countries that have grown weary of Western institutions’ condition-heavy loans and hegemonic voices, countries that wish to join a new Beijing consensus based on voluntary participation, pragmatism and good governance that delivers tangible results – albeit often in a nondemocratic fashion. At the same time, the BRI is hardly altruistic, and any friendship that comes with the BRI is seriously conditional– ultimately, it serves to buttress China’s own national security interests, be it through international and domestic economic growth, potential military expansion, safeguarding food and energy security, or spreading positive influence and image through emerging regions in the Global South. Understanding the BRI as a political instrument of power will help us find entry points for negotiations and leverage – for example, emerging economic partners of China along the BRI that have grown tired of debt might voice their dissent to great effect, as Malaysia had recently done, knowing that the BRI, as the vehicle of China’s 21st century grand strategy is unlikely to go away, and that China, principally concerned about its own image and influence abroad, will seek to renegotiate and appease unrest rather than take hardliner punitive actions.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have presented the BRI through three analytical lenses – and three distinct intellectual disciplines – environmental science, environmental economics and international relations.

The environmental science lens presents a picture of the BRI that is mixed in terms of its environmental impacts but leaning towards more harm done than benefits reaped. While transfer of sustainable development technologies and the increase in socioeconomic development in BRI countries can present opportunities for environmental protection, the BRI is filled with environmental concerns, ranging from disruption of local ecosystems, excessive use of water resources, uncontrolled population growth, exportation of shadow ecology principally in the form of coal-fired plants and system contributions to greenhouse emissions and thus climate change.

The environmental economics lens explains in detail the financial sources of the BRI – largely Chinese-owned state banks, SOEs and MDBs with heavy Chinese influence. This lens illustrates the lack of public-private balance, as well as financial input and independence from emerging economies along the BRI, and problems associated with Chinese dominance and even economic imperialism, such as the lack of commitment to strict environmental regulations and frameworks. The lens also presents opportunities for green finance to engender systemic change to the BRI, particularly if “co-benefits” – where China’s green policies abroad reap economic benefits – are in play.

Lastly, the international relations lens focuses on explaining the overarching design behind the BRI, and how the BRI helps materialize China’s grand strategy. It explains China’s interests and concerns in nontraditional security, particularly energy security, which are a major driving factor for the BRI’s implementation. It also explains China’s grand strategy of expanding its soft power in efforts to assume hegemony within the international system, as counterweight to or even replacement of the US, through economic imperialism throughout the BRI, consolidation of allies and construction of images of positive reputation and legitimate leadership.

This paper argues, using Pacey’s concept of “technology-practice”, that the BRI must be approached through a multidisciplinary perspective, because no singular analytical lens can explain or predict the future development of both the project and China as well as the international system as a whole; the sum of the parts is bigger than the whole in this case study. The lenses of environmental economics and international relations, however, also offer areas for future research, such as the effectiveness of green finance in engendering sustainable development, the effectiveness of economic “co-benefits” for green finance, China’s own financial risks in committing large-sum investment loans and the effectiveness of the BRI in expanding China’s soft power and legitimacy as a rising global leader. I further argue that the international relations lens is even more important than the economic lens, thus and should ultimately be the anchor of any multidisciplinary approach to the BRI, because any issue surrounding the BRI, controversial or otherwise, is ultimately underscored by Chinese grand strategic interests of counterbalancing the US-led world order and expanding its own positive image and influence abroad. Finally, I argue that there is also a need for more on-the-ground case studies that provide more insight into the actual and projected environmental impacts of the BRI, as well as changes in legislative and legal environments along BRI countries.

References

Greening the belt and road initiative. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from http://www.sustainablefinance.hsbc.com/our-reports/greening-the-belt-and-road-initiative

Hafeez, M., Chunhui, Y., Strohmaier, D., Ahmed, M., & Jie, L. (2018). Does finance affect environmental degradation: evidence from One Belt and One Road Initiative region? Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1317-7

Li, P., Qian, H., Howard, K. W. F., & Wu, J. (2015). Building a new and sustainable “Silk Road economic belt.” Environmental Earth Sciences, 74(10), 7267–7270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-4739-2

Tracy, E. F., Shvarts, E., Simonov, E., & Babenko, M. (2017). China’s new Eurasian ambitions: the environmental risks of the Silk Road Economic Belt. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 58(1), 56–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2017.1295876

4 Ways China’s Belt and Road Initiative Could Support Sustainable Infrastructure | World Resources Institute. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from http://www.wri.org/blog/2017/05/4-ways-china%E2%80%99s-belt-and-road-initiative-could-support-sustainable-infrastructure

Belt and Road Initiative. (2017, September 27). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from http://www.paulsoninstitute.org/economics-environment/paulson-primers/belt-and-road-initiative/

Greenovation Hub. (2016). Exploring the Overseas Environmental and Social Risk Management by Financial Institutions under “The Belt and Road Initiative”. http://www.ghub.org/cfc_en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/04/br_report_201608_en.pdf.

Friends of the Earth. (2016). China’s Belt and Road Initiative: An Introduction.

Green Finance Committee (GFC) of China Society for Finance and Banking. (2017). Environmental Risk Management Initiative for China’s Overseas Investment.

Gill, I. (2017, September 22). Future Development Reads: China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2017/09/22/future-development-reads-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/

Greening the Belt and Road. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://www.chinadialogue.net/blog/10149-Greening-the-Belt-and-Road/en

Green Finance Initiative. (2017). Greening the Belt and Road. Retrieved from http://greenfinanceinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Greening-the-Belt-and-Road-English.pdf

Technology, E. I. P. and. (n.d.). The China Belt And Road Initiative Could Help – Or Hurt – Clean Energy In Emerging Economies. Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/energyinnovation/2017/12/04/the-china-belt-and-road-initiative-could-help-or-hurt-clean-energy-in-emerging-economies/

The Belt and Road Initiative: Progress, Problems and Prospects. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://www.csis.org/belt-and-road-initiative-progress-problems-and-prospects

Belt and Road Initiative to help countries achieve UN goals: official – World – Chinadaily.com.cn. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2017-12/05/content_35220754.htm

China’s Belt and Road Initiative to spur green, resilient growth in Africa: Expert – Chinadaily.com.cn. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201712/09/WS5a2b2c31a310eefe3e99f01c.html

Diplomat, A. C., The. (n.d.). The Belt and Road Initiative and the Future of Globalization. Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://thediplomat.com/2017/10/the-belt-and-road-initiative-and-the-future-of-globalization/

Du, M. M. (2016). China’s “One Belt, One Road” Initiative: Context, Focus, Institutions, and Implications. The Chinese Journal of Global Governance, 2(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1163/23525207-12340014

How China can green its belt and road projects. (2018, January 21). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from http://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/2129647/how-belt-and-road-initiative-can-be-chinas-path-green

Len, C. (2015). China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative, Energy Security and SLOC Access. Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 11(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09733159.2015.1025535

Manuel, A. (2017, October 17). China Is Quietly Reshaping the World. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/10/china-belt-and-road/542667/

President Xi Jinping’s “Belt and Road” Initiative. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/president-xi-jinping%E2%80%99s-belt-and-road-initiative

TWQ: China’s Unraveling Engagement Strategy – Fall 2013. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/twq-china%E2%80%99s-unraveling-engagement-strategy-fall-2013

Will China’s Belt And Road Initiative Help Or Hinder Clean Energy In Fast-Growing Nations? (2017, December 12). Retrieved February 27, 2018, from http://www.theenergycollective.com/energy-innovation-llc/2418188/will-chinas-belt-road-initiative-help-hinder-clean-energy-fast-growing-nations

French, H. W. (2017). Everything under the heavens: Empire, tribute and the future of Chinese power. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Pacey, A. (1983). Technology: Practice and culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

CPEC: China to get 91% of the Gwadar Port income for next 40 years. (n.d.). Retrieved April 11, 2018, from https://timesofislamabad.com/25-Nov-2017/cpec-china-to-get-91-of-the-gwadar-port-income-for-next-40-years

Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road. (n.d.). Retrieved April 27, 2018, from http://en.ndrc.gov.cn/newsrelease/201503/t20150330_669367.html

Gallagher, K. S., & Qi Q. (2018). Policies Governing China’s Overseas Development Finance: Implications for Climate Change. The Center for International Environment & Resource Policy.

Who is Financing the New Economic Silk Road? – Silk Road Briefing. (n.d.). Retrieved April 27, 2018, from https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2017/09/21/financing-new-economic-silk-road/

Ikenberry, G. J. (2008). The Rise of China and the Future of the West: Can the Liberal System Survive? Foreign Affairs, 87(1), 23–37.

Ikenberry, G. J. (2011). The Future of the Liberal World Order: Internationalism After America. Foreign Affairs, 90(3), 56–68.

Younger, M., Morrow-Almeida, H. R., Vindigni, S. M., & Dannenberg, A. L. (2008). The Built Environment, Climate Change, and Health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(5), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.017

Gill, B. (2010). Rising Star: China’s New Security Diplomacy. Brookings Institution Press.

Schultz, K. (2017, December 12). Sri Lanka, Struggling With Debt, Hands a Major Port to China. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/12/world/asia/sri-lanka-china-port.html

With Sri Lankan port acquisition, China adds another “pearl” to its “string” – CNN. (n.d.). Retrieved April 27, 2018, from https://www.cnn.com/2018/02/03/asia/china-sri-lanka-string-of-pearls-intl/index.html

Full text of President Xi’s speech at opening of Belt and Road forum – Xinhua | English.news.cn. (n.d.). Retrieved April 27, 2018, from http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-05/14/c_136282982.htm

Forbes. (2014). Take A Trim Tab Approach To Climate Change. Retrieved April 27, 2018, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/hbsworkingknowledge/2014/09/24/take-a-trim-tab-approach-to-climate-change/

Dauvergne, P. (1997). Shadows in the Forest: Japan and the Politics of Timber in Southeast Asia. MIT Press.

Qi Hang can be contacted at qihang@u.yale-nus.edu.sg.