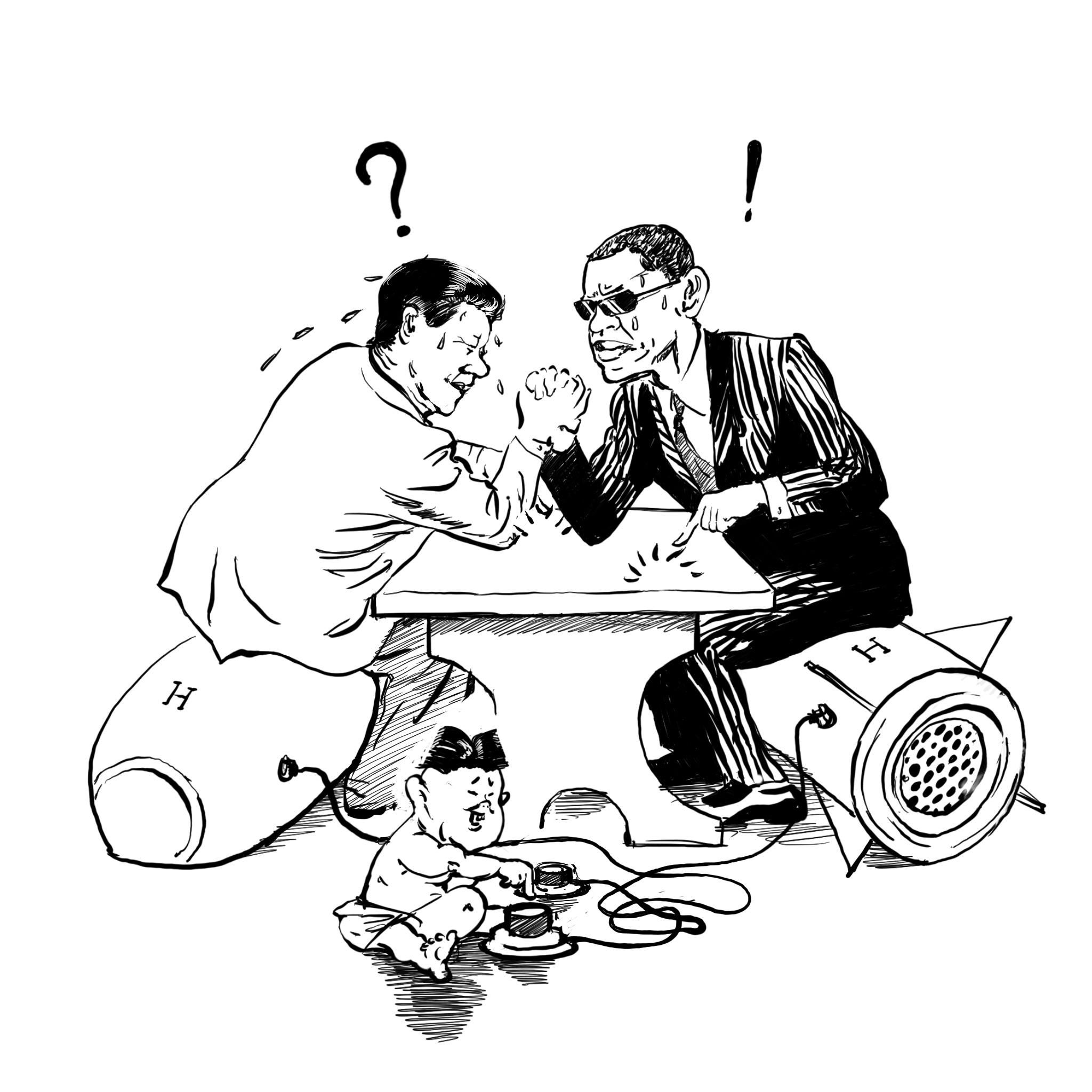

CAMILIA RAZAVI and DANIEL KHALESSI explain the paradox that has kept China from denuclearizing North Korea.

At approximately 9:00 a.m. local time on September 9th, 2016, seismologists around the world detected a 5.3-magnitude earthquake in North Korea’s northernmost province near the Chinese border. The US Geological Survey and nuclear weapons experts determined that the seismic activity was the result of a nuclear explosion at Punggye-ri, North Korea’s underground site for its four previous nuclear weapons tests. The 10-kiloton nuclear explosion—North Korea’s largest known test to-date—met swift condemnation from the international community, including China, its long-time ally and largest trading partner.

China has served as North Korea’s most important military ally since the beginning of the Korean War. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, “China provides North Korea with most of its food and energy supplies and accounts for more than 70 percent of North Korea’s trade volume.” Despite the history of close military and economic relations, China has major concerns about North Korea’s nuclear program.

The recent nuclear test has led the international community to zoom in on some of the complexities in relations between the two nations. However, misaligned interests between the US and China over the future of the Korean Peninsula and the dynamics of China’s relationship with the Kim regime make it challenging for both sides to find a sensible policy outcome.

“North Korea believes that China is helping them primarily because it is in China’s self interest to do so,” says Philip Yun, Executive Director and Chief Operating Officer of the Ploughshares Fund, a foundation that supports initiatives to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. “China doesn’t want a collapse in [North Korea’s] government which could allow US troops to have direct access to the Chinese border—the very reason they fought in the Korean War to begin with.”

Further complicating US-China relations, the United States is moving swiftly to deploy the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense system (THAAD) into South Korea. THAAD is meant to protect South Korea against a possible attack from Pyongyang by intercepting ballistic missiles in their terminal phase of flight. China vehemently opposes THAAD, seeing it as yet another threatening encroachment by the United States in the Korean Peninsula.

Following North Korea’s fourth nuclear test in January and long-range ballistic missile test in February, Chinese leaders criticized North Korea’s actions and advocated for international diplomacy to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula. China has generally opposed multilateral economic sanctions against the North Korean regime, believing that crippling sanctions could exponentially increase the probability of the regime’s collapse. Chinese leaders also fear that the North Korean regime’s downfall would inevitably lead to a mass refugee influx across the 1,420-kilometer border between the two countries. American policymakers, however, want China to implement sanctions to pressure North Korea to abandon its nuclear weapons program.

“It seems increasingly clear that as long as this difference between China and the United States continues, it will only give North Korea more time to advance its nuclear and missile technologies,” says Choe Sang-Hun, a Pulitzer Prize-winning South Korean journalist and expert on US-Korea relations. “If China and the United States want a nuclear-free North Korea, as they have repeatedly said they do, they must first work out a common strategy to achieve that goal.”

The rhetoric and actions of Chinese leaders in the aftermath of North Korea’s latest nuclear test, however, suggest they might be considering more stringent policy alternatives.

On September 9, Xinhua—the official news agency of the Chinese government—reported that the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs believed the nuclear test was “unwise” and contravened United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions. Moreover, on September 19, President Obama and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang met in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly. At the UNSC meeting, the two leaders discussed strengthening cooperation and investigating Liaoning Hongxiang Industrial, a Chinese conglomerate that is allegedly providing financial support to North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

Although China has not publicly announced its support for greater economic sanctions against North Korea, American and Chinese diplomats are discussing the possibility of a new UNSC sanctions resolution. According to Bloomberg, the US and China are engaging in private negotiations over whether to impose restrictions on North Korea’s energy trade in coal, iron ore, and crude oil. Experts disagree on the next steps the United States should take with North Korea. In a speech at the Council on Foreign Relations on October 25, the Director of National Intelligence in the U.S., James R. Clapper Jr., said that denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula was “a lost cause.” Some experts, however, argue that the United States should engage in diplomatic negotiations with North Korea with clear-cut, sequential priorities—starting with the halting of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program as opposed to its elimination.

“We should focus on the future. Get together with China and see what it’s priorities are — such as halting the program, rather than trying to get North Korea to give up the nukes now,” says Dr. Siegfried Hecker, Senior Fellow at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation and the Former Director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Dr. Hecker, who has been invited by North Korea multiple times to visit its nuclear facilities, believes that diplomacy is a feasible option.

“The North has given many indications in the past that it is willing to discuss various limits on its program. The US government should take it up on such proposals,” Dr. Hecker tells China Hands. “Negotiating the elimination of nuclear weapons will take a long time—it will have to be ‘halt, roll back, and eventually eliminate’—that will take many years.”

On October 4, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that the United Nations should act in a manner “conducive to solving the nuclear problem on the peninsula and maintaining peace and stability.” As of now, however, it is unclear what specific policy prescriptions such a posture would entail. In formulating such a policy, Chinese leaders will have to weigh their concerns regarding the North Korean regime’s stability with the importance of sending a clear and credible signal to the North Korean regime against its nuclear weapons program.

Camilia, a UC Berkeley graduate, is an Operations Associate and Executive Assistant to the COO of Ploughshares Fund and a former intern at the White House under the Obama Administration. Contact her at camiliarazavi@gmail.com.

Daniel is Co-Founder and CEO of Fireside. He is an alumnus of the Yenching Academy, Yale’s Masters program in global affairs, and Stanford University. He has worked at the US Mission to the UN and the US Department of Treasury. Contact him at daniel.khalessi@aya.yale.edu.

Illustration // Kaifeng Wu